It has been suggested that tribalism is the reason for the tragic history of Nigeria since Independence in 1960. See Margery Perham's weasel words in Sir James Robertson's 'Transition in Africa', an apology for treachery and treason.

The very occupation of a territory with politics banned must, I suppose, bottle up tensions and suppress real or imagined discord. Meanwhile, totally irrelevant issues are made meaningful. What is real to the occupying power, like a war, affects the Colony because the local administration wills it. So l00,000 Nigerian men served in the British Army in the Second World War, mainly in the Far East. My clerk, Mr Fadeyebo, was ambushed by the Japanese and wounded while floating on a river raft in Burma. When the survivors were rounded up on the riverbank, the British officers and men were bayoneted by the Japanese. When a Japanese officer approached Fadeyebo, he feared the worst, but the officer said, "This is not your war, black man, we are not at war with you", and he was left with the other wounded Nigerians lying under the trees. Two of them survived. (The experience of war must have affected those of the 100,000 Nigerian soldiers who survived, but although important, this fact is irrelevant to my present concern.)

We are often told that the aim of British foreign policy has long been a unified Nigeria. Those of us who lived in Nigeria before Independence might question the truth of that because we recall how the British governed strictly in accordance with the maxim of 'divide and rule'.

The manner in which 'Nigeria' was created was of course the responsibility of the British, not of the millions of Africans of hundreds of tribes who one day found themselves contained within straight lines drawn on the map of West Africa, and told they were subjects of the Great White Queen. A great event for a young African who could now, if a missionary came to his village, go to a missionary school, become a Christian, get a job as a Government clerk and own a bicycle. Other events would mould him, events largely dictated by men in a foreign land, as a foreign war had taken Mr Fadeyebo to Burma. If a clerk was befriended by a sympathetic British administrator in the rush to Independence in the late 1950's, he would find himself sitting behind that white man's desk at Independence, living in a European house with servants and a brand new Ford Consul parked outside.

If unity is required, do you exacerbate tribal differences by dividing the nation on tribal lines, creating a Northern Hausa/Fulani Moslem State; a Western Yoruba, Moslem/Christian State; and an Eastern Igbo Catholic Christian State? Do you confine missionary activity to the South so that the Moslem North has no schools, and all the educated Africans who staff the Government civil service come from the South and are mainly Catholic Ibo? When the educated South inevitably produces nationalist leaders, do you, seeing the danger to the feudal backward North, provide an educational system in the North? The problem was ignored and nothing was done.

It seemed to the disinterested observer before Independence that the British did everything to emphasise and exacerbate tribal differences. Even the system of rule and administration was different. Indirect rule in the North confirmed the power of native chiefs, who naturally found that their interests were identical to the British. In the South the British could speak in English to the missionary-trained locals, which might be a mixed blessing when the village bright boy returned from London with better degrees in British law than the big white chief, who often made up the law as he went along. (British officials had to learn a local language to pass a promotion bar. A thankless task because when he had passed he would be promoted to a region where his newly acquired language was useless.)

At one time, so strong was the split between North and South, that separate stamps were printed. The different policies, systems, languages had their effect on the British rulers. Those in the South encouraged the missionary schools and inspected them. Work had to be found for school leavers, and public utilities and plantations sprang up to absorb them. Clean water, electricity supplies, dispensaries and roads followed in the wake of enthusiastic British administrators, who were dubbed 'nigger-lovers' by their less active polo-playing colleagues in the feudal North.

We must not labour the point. The North, West and East were not truly separate countries. Lagos, more or less, ruled them all, and Lagos was controlled in turn by Whitehall. Take away the brakes on political activity, have three Prime Ministers each leading his own 'tribe' and each looking to the British overlord for fair play, equal treatment and perhaps occasional favours in return for loyal behaviour, and any pretence of unity might disappear, especially when a scramble starts to be the privileged one to whom the British would hand over the keys of the whole kingdom.

The other major assumption shared by all commentators was, of course, that the British would hand over power without fear or favour to whichever political party commanded a majority in the second and final stage of the Independence elections which took place in 1959.

It was true that the British always got on well with the leaders of the Moslem (and to a degree pagan) North. This was well known to be so, and no one would bother to deny it. The Northern chiefs were so happy with British rule that they did not want the British to leave at all, particularly so if the bolshie Southerners, whom the Northerners loathed almost as much as their British administrators - if that were possible - were to take over in Lagos. Naturally the British did not wish to upset their Northern friends. It was even said by the British that if the Northerners were not guaranteed freedom from rule by the Southerners they might march on the South and drive the despised missionary-trained bolshies into the sea. It was left unclear whether the chiefs would do this themselves or whether they would depute the task to their British advisors.

Was this to be an intractable problem? It will be seen that if the North won the national elections, there would be those who would suggest that the British had favoured the North and given them a helping hand. Poor losers of course. However, if the North were to win it would solve what might otherwise be a terrible problem.

Not everybody trusted the British, but nobody cared what the communists said. Uncle Joe did not get where he did by winning elections either. As for the Fabians and other do-gooders, their doubts were quashed by the very fact of Independence being granted at all. Had not they campaigned for this in so many pamphlets and speeches? It was almost unbelievable and euphoria short-circuited their critical faculties. Even the British had been happy to confess to imperialism and an empire won by conquest, but suddenly it all became a sacred trust which had been accomplished. It only remained to see to which of the carefully trained and nurtured responsible leaders we would hand on the sacred flame. More succinctly the creeps were at long last going to be paid off.

It was true that successive Governors General had found the southern nationalists, led by Zik in the East and more parochially perhaps Awo in the West, a bit of a trial. Zik had just emerged from a Government enquiry into his running of a bank. He had not been exactly cleared but neither had he been jailed, and a more subdued and perhaps wiser Zik, after winning a vote of confidence in a fresh election in the East, seemed prepared to co-operate with the British.

Nigerian statistics were always a bit problematical. My own experience as head of the statistics branch at the Department of Labour had not been reassuring. The number of unemployed in Nigeria - a derisory figure which British politicians would have envied - on slightly closer examination turned out to be the total calling in at the handful of Labour Exchanges in the larger towns.

A possible insoluble problem suddenly loomed less large when the British announced that the North contained 50% of Nigeria's population. What had seemed to be a three-legged race now seemed to be something else. The NPC ruled the North with little opposition, but the West and East were at each other's throats. The North could be unbeatable. The only question was which of the southern leaders would decide to throw in his lot with the North. A Zik in opposition could be dangerous, but a new less belligerent Zik might be safer in Government. One might have thought a largely Moslem West would get along better with the Moslem North, and indeed, once the tragic and futile Biafran war started, such an alliance would come about.

If the British in Whitehall had been able to influence events, these were the thorny problems they would have mulled over. Had they done so, the right man was available to advise, because a former Governor General, Sir John MacPherson, was the top official. If anyone advised Harold Macmillan on Nigeria's possible intractable problems, it was Sir John.

If Sir John disliked Zik, he positively loathed Awo whom he regarded as a smart arse. Awo had responded to the news, which must have been a blow, that the North would have 50% of the votes, with a cheerful resolve to take the war into the North with a small army of election agents and propagandists. Awo had modelled his party machine on the British Conservative Party, and he was to command his troops from a helicopter, from which he would descend and perhaps seem like a god to the simple northern peasant. Awo's plans were noted by the new Governor General with some dismay. Was this another intractable problem looming on the horizon?

Whatever ideas Whitehall came up with to ease the transition, one big decision was taken. It might have been thought desirable to leave everything to the experienced men on the spot. On the other hand, if there were intractable problems, would the experienced men on the spot necessarily be the right men? Even top officials could get to love the country and its people. Tough decisions might need tough people who could take an overall view without sentiment. There were liberals in the Colonial Office, but very few in the Foreign Office. The Foreign Office ran the Sudan and when the Foreign Office cracked the whip the Sudan administrators jumped on the Sudanese. Not everyone trusted these tough ex soccer blues to observe the rules when it came to Sudan's turn to hold elections, and the presence of international observers was insisted on. It is a tribute to the reputation of the British in Nigeria that no one questioned their ability to run honest elections. Not that there had ever actually been any elections to speak of, but that was perhaps the reason no one questioned the honesty of the British. They were after all granting elections and they were going to go! Quit! Exit! Depart forever! No more Governor General in white suit and plumed hat. No more Government House tea parties. No more Union Jacks and Empire Day. No more Residents and District Officers to kow-tow to. Already these local and powerful gods were being renamed Local Government Advisors! What a come down. Little wonder, except in the North, that they deserted their sacred trust almost to a man in favour of the generous compensation lump sum and pension. Or was there a more sinister reason for the defection of these dedicated officials? Had they been ordered to cross a bridge too far?

In came experienced Sudanese officials as Governor General in Lagos, Governor in the North and Chairman of the Public Service Commission. Tough policies might produce casualties and a strong man running the Commission to which unhappy British civil servants would appeal, was a sound precautionary measure. A new Governor in the East rounded off these precautionary measures in the run up to the General Election, which would be in two stages, at Regional (State) level and finally at the Federal and National level.

Unity was now the overriding theme, and it was sensible that it should be so. Precious little had been in evidence during British rule. This great nation not only contained one quarter of Africa's black people, it was in West Africa, unique in having no permanent white population, not one, as white settlement had been banned as the region was so unhealthy. Other colonies amounted to nothing against this giant. Nigeria would be the major force in black African politics. Economically it was rich and would be extremely wealthy when its newly-discovered rich oil fields came on stream. What is not often realised was that the bulk of the British Colonial Service - a misnomer really - was employed in Nigeria. As the colonies employed and paid the officials, only a small secretariat ran the Colonial Office and they were from the Home Civil Service. The so-called Colonial Service was really a small recruiting office, mainly charged with finding decent people to work for small pay in often awful and unhealthy conditions in Nigeria.

But was the necessity of unity being used to cloak some tough policy decisions? Certainly when I questioned British policy in Nigeria in an interview in 1960 with the Governor General, Sir James Robertson, I got a very tough answer. No one could be really surprised when the North won the Federal Elections in 1959. Quickly, the Governor General - even before the results were all in - declared the North the winner and as rapidly blessed an alliance with Zik's party, the NCNC.

I was not at all surprised for I knew, even before the 1956 State elections at Regional level, that this was how it was going to be. The Governor General in 1960 confirmed to me what he had let me know in 1956. There had been an intractable problem and means had been found to resolve it. Unity had made this necessary. The Northern census results were to be challenged in many ways, but they were never to be confirmed or accepted as accurate, and that is still the position thirty years on.

Was that all the necessary action to be taken? Had Zik not been brought to heel with a carefully prepared Bank Enquiry that could easily have jailed him? A close friend of Zik told me more than I can reveal. When I questioned him, as I was a great admirer of Zik at the time, he said,

"The next time there is trouble, Zik will be abroad. He will never be caught as he will always have an alibi."

"What cynical rubbish," I replied.

Having said that, my friend was clearly wrong when it came to the Bank Enquiry, because the British nearly nailed Zik, whether they were justified or not.

After that close brush with the law, a great manipulator took control of Zik's party. Zik had made many great personal sacrifices for his NCNC and had personally financed it for years at great personal cost. Now he was broke and someone who could raise vast sums of money, as if from thin air, would be the real power-broker in Nigerian politics. Chief Festus Okotie Eboh - 'Festering Sam' - was not only a very cheerful character and master crook, he was much loved by the British in Lagos and Whitehall. Okotie Eboh was not his real name - he thought it sounded good. Like Robert Maxwell, not much about him was what it seemed. Like Maxwell too, he was greatly feared and he was also a great wheeler-dealer. The Governor General knew him to be a thief, a master criminal, a trickster, someone totally corrupt. He was also something of a rapist. Not the first person one might think to be made Minister of Finance by the British, after a spell as Minister of Labour.

The NCNC made him Party Treasurer and British officials, principally Charles Bunker, a Senior Labour Officer, were ordered by the Governor General to extract large donations from multi-national companies for the NCNC and NPC. Thus, in 1956, four years before Independence, Government-approved corruption was institutionalised and at a national level by the British. This was the first lesson in democratic politics that the British taught Nigerian politicians. As the NPC in the North were inexperienced in these matters, the British arranged their finances, so they came from Native Administration (local Government) funds. Okotie Eboh thought big, and decided when he became Minister of Labour that he owned the Ministry, so why should he not sell its offices if he chose? He sold a prime office site opposite the Lagos Railway Station to a company, which had long had designs on the site. The Governor General had him over at Government House and told him to be more circumspect next time as people were talking! The importance of Okotie Eboh was that he was the man who could use his newly-acquired wealth to weld the Northern NPC and the Eastern NCNC together. The wedding actually took place with the blessing of the British in 1956 before even the first stage of the Independence Elections. I was a witness at this wedding. It was about unity, and two totally different parties coming together in a partnership to solve an intractable problem. It was a secret wedding and most people believed it took place in 1960 after the results of the Federal Independence Elections were announced.

Awolowo was to pay a big price for being rude to the British and being a smart arse. The British wanted revenge. That very word was to be used, although when Sir James Robertson recorded it, he said it was only natural that revenge against Awo should be sought by the parties who formed the Government. As to why anyone should seek revenge on Awo, Sir James could only suggest that he had invaded the privacy of the Northern Chiefs' harems by flying overhead in a helicopter. The real truth was that he had actually dared to send the British to Coventry and his Party would not speak to British officials! Presumably it was because of this helicopter prank that the British harassed Awo's Action Group when it campaigned in the North and meted out brutal treatment, including turning a blind eye to the murder, of AG campaign workers.

It was in the name of unity that the British Government rigged the Nigerian Independence Elections most successfully from start to finish. I almost wish that Sir James Robertson had not placed his trust in me and confided to me the British Government's plans in 1956 before the elections took place. It put a very heavy and grave responsibility on my shoulders.

RETURN

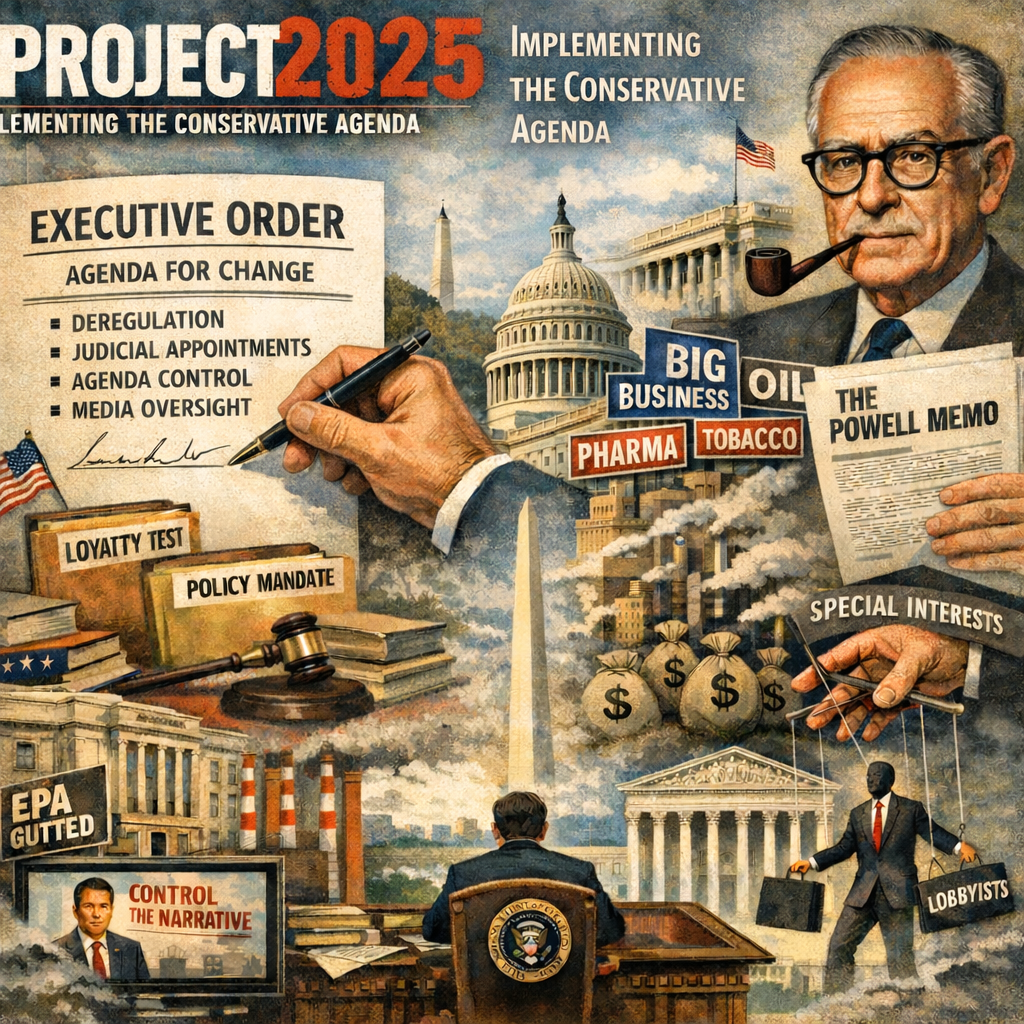

From the Powell Memo to Project 2025: How a 1971 Corporate Strategy Became a Global Template for Power In August 1971, a corporate lawyer named L...

The Market’s Mood Ring: How Volatility Across Assets Traces a Hidden Geometry of SentimentIf you want a fast, honest way to describe modern markets,...

Nigeria’s grid collapses are not ‘bad luck’ – They are a design failure, and we know how to fix themFirst published in VANGUARD on February 3,...

Islands of Credibility: Nigeria’s Best Reform Strategy Starts in the StatesFirst published in VANGUARD on January 31, 2026 https://www.vanguard...

Project 2025 Agenda and Healthcare in NigeriaThe US and Nigeria signed a five-year $5.1B Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on December 19, 2025, to bo...