Down the ages, several political "isms" have vied with one another for popular acceptances: feudalism, anarchism, capitalism, syndicalism, socialism, Trotskyism, etc. Only two of these "isms" have survived the age-long contest and are at all worth considering in this lecture.

Capitalism is an economic system, which is founded on the principle of free enterprise and the private ownership of the means of production and distribution. The protagonists of capitalism claim that its essential characteristic is economic freedom. The producer is free to produce whatever goods he fancies; but the consumer is equally free to buy what he wants. There is a market mechanism under this system, which brings the producer and consumer together and tends to equate the supplies of the one to the demands of the other, and harmonise the whims and caprice of both. It is this same market mechanism, which determines what prices the same market mechanism, which determines what prices the consumers pay to the producers as well as what share of the total output, in cash or in kind, goes to each of the four recognised factors of production - e.g. Land, Labour, Capital and Organisation. It is further claimed for this system that every person is capable of watching his or her own interest, and that whatever injustice may appear in the short run to have been done by the operations of the market mechanism, in the long run this mechanism tends to bring about a state of equilibrium between the producers and consumers as well as among the factors of production, and to give to each of them a just and adequate treatment and reward.

I do not think it is necessary, at this point of time, and especially to this scholarly audience, to set out the theoretical arguments against these claims. It is enough to asserts that economic history has shown that the market mechanism, otherwise known as the mechanism of supply and demand, is a blind and utterly impersonal social apparatus, within the framework of which the strong, clever, and unethical few have, more often than not, taken undue advantage of the many who are weak.

Capitalism is at its best when it is planless. But in these modern times, the laissez faire type of capitalism is now restricted mainly to most of the undeveloped countries in Africa and Latin America. But in many parts of the so-called Western Democracies, the state has been intervening to smooth some of the rough and inhuman edges of capitalism. Anti-monopoly laws, which in practice, it must be admitted, have proved ineffective, trade union law, minimum wage law, factory legislation, tax laws, death duties, finance measures, social and insurance laws - all these and more are some of the means by which many modern states have stepped in to regulate and humanise capitalist activities.

By these means the state, in a capitalist society, has to some extent helped in directing the operations of the market mechanism in all its ramifications, and in particular in regulating the distribution of national income among the factors of production in order to ensure a state of affairs, which is nearer to equity and equilibrium than is the case under a laissez faire capitalist system.

Negatively, socialism is opposed to capitalism. But positively, it is firmly rooted in the principles of public ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange and of economic planning. One of its cardinal aims is that every labourer - be he a professor, lecturer, teacher, minister of religion, minister of state, civil servant, lawyer, doctor, engineer, farmer, road worker, or carrier - shall get his or her due hire, and that no one, however, powerful or specially circumstanced, shall get any more than that. Socialism seeks to bring the ennobling principles of ethics to bear upon the operation of economic forces.

Consequently, it may be said that the overriding aim of Socialism is to bring about an economic commonwealth in which the needs of all, regardless of birth and station in life, as opposed to and distinct from the profit-making desires of some, will be satisfied. In other words, under Socialism, the aim is that capacity shall have its adequate reward, but also that those who, for any cause, are incapacitated from, or have not yet grown up enough to participate in productive activities shall not, on that account, suffer misery.

I am not a Marxist myself. But what Marx says in this connection and which is true, is well worth bearing in mind by those who plan for the welfare of the people. 'Under the capitalist system,' says Marx, 'the economic nexus between man and man is wholly dominated by naked self-interest.'

To even up, I would like to refer to what Adam Smith says on the same point from an opposite standpoint. Says he: 'Every individual is led by an invisible hand (that is self-interest) to promote an end (that is the common good), which was not part of his intention.'

To sum up in well-known socialist slogans, the aims of Socialism include social justice, equal opportunity for all, respect for human dignity, and the welfare and happiness of all, regardless of creed, parentage, and station in life. In other words, under socialism the nexus between man and man is wholly dominated by equality and fraternity and by the needs of the under-privileged.

There are two kinds of socialism: revolutionary socialism and democratic socialism. Revolutionary Socialism is what is generally known as Communism. Its aims are the same as those of democratic socialism. But the orientation of the communist is different from that of the democratic socialist. This difference in orientation consists in the divergent method of approach to the realisation of socialist ideals. The communist believes that the political power of the state as well as the economic power of the capitalists should be seized by revolutionary actions, and that in their places 'dictatorship of the proletariat' should be established.

It is common knowledge that the capitalists, who are invariably in control of a capitalist state, will not yield ground to the communists without the stiffest possible resistance. The communists, on the other hand, are inflexibly determined to break any such resistance at all costs. Result: the prelude to the advent of communism in the countries where this system is practised has always been a bloody revolution.

On the other hand, the democratic socialist believes, and sincerely so, that the ends of socialism can be attained by democratic means. The essence of democracy, however, is the consent of the majority, which shall be expressed freely, and without any form of coercion. Since the cornerstone of socialism is the conversion of private ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange, to public ownership, it follows that under democratic socialism such conversion cannot be done wholesale in one fell swoop. It also follows that every conversion, when made, shall be accompanied by the payment of fair compensation.

There are those who believe that revolutionary socialism is preferable to democratic socialism. In the one case, the action is said to be quick, and the new era is ushered in, in all the sectors of the economy without much delay. In the other, processes of debate, persuasion and negotiation are considered cumbersome and slow, and easily liable to sabotage by the capitalists, who are very agile and ruthless in bargaining, and who will have no qualm of conscience whatsoever in perverting the electorate, if need be, against the latter's own best judgement and interests.

All those who have read their history aright will agree that the bringing about of revolutionary socialism can also be protracted as well as a bloody business. What is more, the inevitable consequences of the venomous hate, violence and carnage which, preceded the advent of revolutionary socialism are, in my humble opinion, so horrible and sickening that they should never be generated by mere doctrinaire imitations or propensities. The point must never be overlooked by the protagonists of revolutionary socialism, that it was the appalling conditions of the masses, in the face of a fabulously rich and tyrannical few, which existed in the countries of Russia (not any more) and China where communism now flourishes, that provoked a violent rebellion. This should not at all be surprising. For as Bacon says, 'rebellions are caused by two things: much-poverty much-discontent; rebellion of the belly is the worst.' It must be frankly admitted, therefore, that the communist revolution in Russia and in China is historically justified. It must be plainly 'the rebellion of the belly.'

Speaking for my party and myself, I hold the view that the conditions of masses in Nigeria, though very bad in some parts of the federation, are not yet so degrading as to provoke a rebellion or violent revolution. In the circumstances, it is the considered view of my party that the ideals of socialism can be realised in Nigeria by waging a battle of words and wits, rather than by engaging in a clash of steel and an exchange of bullets. By adopting these democratic means, the struggle against the evil forces of capitalism might be protracted, and victory might be somewhat long delayed. But, in Nigerian circumstances, I think it is better so.

It is for all the reasons, which I have given, that my party has opted for democratic socialism. In the words of our Manifesto it is our resolve to:

'Build a democratic socialist society founded on the three principles of national greatness, the well-being of the individual, and international brotherhood. To achieve this socialist society,' the manifesto continues, 'we must realise the latent energy of our entire people, we must get rid of the dead-weight of feudalism, aristocracy and privilege. We must overcome the wastefulness and distraction of tribalism and social injustice. We must remove the crippling effect of a backward and over dependent economy. We must go forward into the mainstream of modern civilisation and world knowledge.'

In concrete terms of the socialist ends, which my party sets out to achieve may be spelt out in detail as follows:

It must be emphasised that none of these ends can be attained without planing, without selfless devotion and severe discipline on the part of those who are elected to formulate and execute policies and programmes and without sacrifice of time, energy and money on the part of the Nigerian citizens. I do not need to expatiate on the last two factors. They are obvious and speak for themselves. I only wish to stress to the student members of this audience a point, which they already know, that a beggar nation can only invite contempt to itself. If we are intent on building a strong and self-respecting Nigeria, sacrifice of life may sometimes be required from us in addition to that of time, energy and money. Under communism, planning is totalitarian; the individual counts for little if at all; it is the state that matters; whilst the motive for profit-making is completely disregarded and stifled. On the other hand, under democratic socialism, planning is done by a popularly elected government, which attaches the greatest possible importance to the welfare of the individual citizen. The profit motive is not fully suppressed but where it is given scope it is controlled and harnessed for the common good. Since the public and the private sectors of the economy exist side by side in a democratic socialist state, any planning must of necessity have three prongs. Firstly, the private sector must be controlled, directed and challenged by the Government by means of appropriate laws and regulations.

Secondly, in the public sector, the government must so organised and manage its own business enterprises as to ensure, with maximum efficiency and efficacy, the attainment of its objectives. In addition to existing public-owned undertakings, government must by legislation, coupled with negotiation where necessary, acquire new businesses for which fair compensation need not, however, be paid down in cash as is erroneously believed in some quarters. The shares held by the owners of the nationalised enterprises may be exchanged for government bonds, which yield fixed interests to the private owners. If this is done, it will not be necessary, as has been argued, to divert monies, which could have been used for other development purposes to paying compensation for the nationalised undertakings.

Thirdly, the government must deliberately employ the budget for the purpose of influencing the direction of the country's economy for the benefit of the masses. Budgetary measures can be used to stimulate productive activities in times of depression, to promote the production of certain classes of goods, which would not otherwise have been produced, to encourage the siting of industries in areas where they are socially (though not necessarily economically) desirable. Paradoxically enough, it has been most strenuously urged, in quarters where democratic socialism is also professed, that the idea, which I have before stated are too lofty, and that since most of them are unattainable in the immediate present, they should be consigned to the limbo of Utopian dreams. It is the habit of my party not to talk about anything unless it is practicable.

We think that all the ideals, which I have previously mentioned, are practicable. But even if they are not immediately attainable, it appears to me unimaginative and unpatriotic to discard them on that account. No individual or nation can make any progress worthy of note and good report, unless there is a lofty height, a noble objective, which the man or the nation constantly and perseveringly strives after. It has also been seriously suggested that the best way to advance the interest of our country is to tackle one problem at a time and as it arises, and that we would only be perplexing ourselves by formulating a series of objectives and of methods of achieving them, all of which are bound to raise knotty problems of their own. I must say that it is only the mediocre and the fool that can afford to live but one day at a time, without taking as much as a peep into the future. The wise and the prudent, too, cannot live more than one day or even more than one minute at a time. But whilst he is busy coping with the problem of the day, he also aspires to see beyond the curtain that divides today from the morrow, projects his legitimate and conscientious desires into it, and makes concrete plans for the realisation of these desires. I have said on previous occasions, that granting an enlightened and dynamic leadership, the wealth of a nation is the fountain of its strength. The bigger the wealth, and the more equitable its distribution among the factors and agencies, which have helped to produce it, the greater the outflow of the nation's influence and power. I think I have said enough to demonstrate that it is under a democratic socialist system that our national resources can be exploited to produce sufficiently large wealth for the well-being of our people, and for the promotion of our national greatness and international brotherhood. On this score, it now remains for me to say that the outflow of our nation's influence can only be advantageously canalised by the kind of attitude we adopt towards the other nations of the world in general and of Africa in particular.

After a very careful consideration, my party is of the opinion that the foreign policy of Nigeria should, in the main, be independent and should be guided by the following principles:

Within the compass of a lecture such as this, I think I have sufficiently set out the ideals of my party, and its orientation towards these ideals. But the position in Nigeria today as to the ideal of the ruling parties at the Centre and hence of the country, and their orientation towards such ideals, if any, appears to me to be thoroughly confused. The cause of this confusion is not far to seek. The Federal Government lacks definite ideals or objectives and is devoid of ascertainable orientation. From the jumble of Government's words and actions, however, two things stand out unmistakably; at home its ideological orientation is laissez faire capitalism, and in the external sphere it is subservience to the Western Bloc. After Independence, Nigerian's ship of State has, so to say, been launched on an uncharted sea. The imperialist's beaten tracks are no longer good for us, because we had fought for Independence in order that we may be free to cut our own path to greatness and success. I owe it a duty to the more than 40 (110) million citizens of this country, to make the following concluding declarations. The Federal Government is, in my candid opinion, unpardonably woolly about the destination towards which it is steering our ship of State; it is far from being certain, much less precise, about our position on the high seas, at any given time in relation to the ship's compass; and it has, by words and actions cast grave doubts on its professed skill in the twentieth - century art of politico-economic navigation and seamanship.

RETURN

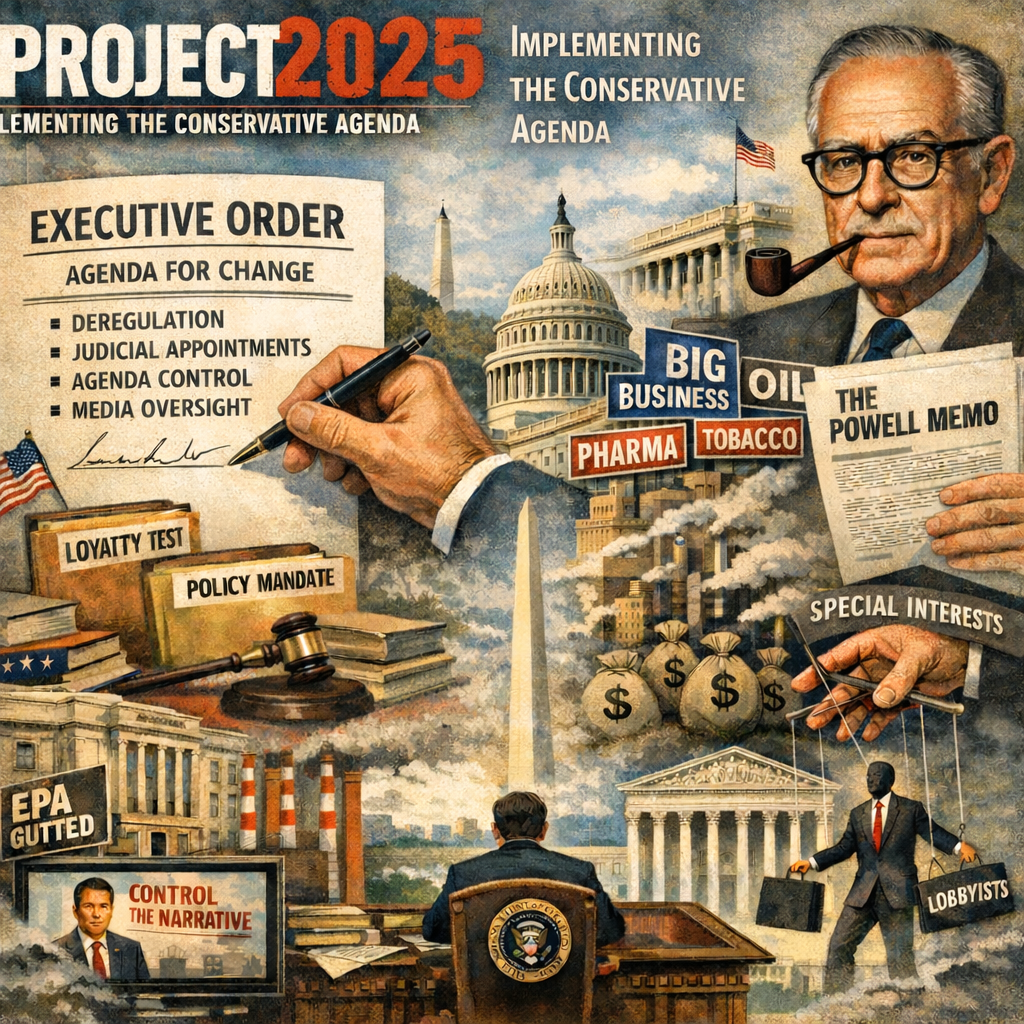

From the Powell Memo to Project 2025: How a 1971 Corporate Strategy Became a Global Template for Power In August 1971, a corporate lawyer named L...

The Market’s Mood Ring: How Volatility Across Assets Traces a Hidden Geometry of SentimentIf you want a fast, honest way to describe modern markets,...

Nigeria’s grid collapses are not ‘bad luck’ – They are a design failure, and we know how to fix themFirst published in VANGUARD on February 3,...

Islands of Credibility: Nigeria’s Best Reform Strategy Starts in the StatesFirst published in VANGUARD on January 31, 2026 https://www.vanguard...

Project 2025 Agenda and Healthcare in NigeriaThe US and Nigeria signed a five-year $5.1B Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on December 19, 2025, to bo...