By

Otive Igbuzor, PhD

Founding Executive Director, African Centre for Leadership, Strategy & Development (Centre LSD) and Treasurer, Centre for Democracy and Development (CDD)

A Keynote Address Delivered at The Memorial in Honour of Late TajudeenAbdulraheem and Late Abubakar Momoh on 3rd June 2024.

1. PREAMBLE

It is both a privilege and a great honour for me to stand before you today to deliver the keynote address as we gather to honour two of Africa’s most distinguished champions of democracy and Social Justice- Late Tajudeen AbdulRaheem and Late Abubakar Momoh. Their legacies inspire us and remind us of the enduring power of ideology, commitment, activism and radical politics in shaping democracy and development in our continent.

In this keynote address, we argue that civil society and social movements can contribute to the deepening of democracy in Africa especially if the organisation is laced with radical politics. I chose to use radical politics instead of contentious politics because I think that Taju and Momoh will prefer radical politics to contentious politics. But first, we explicate the concepts of civil society, social movements and democracy and their status in Africa today.

2. CONCEPTUAL CLARIFICATIONS

a. CIVIL SOCIETY

The concept of civil society (including NGOs) has been variously described by scholars as imprecise, ambiguous, controversial, nebulous and one of the keywords of this epoch.[1]Some scholars have contended that the rise of civil society is associated with strategies of rolling back the state and has contributed to de-legitimising post-colonial nationalism and re-enforcing neo-liberal theories of the separation of State and society. This is probably why civil society assumed more significance with the end of the Cold War in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Civil society plays a very crucial role. Many scholars have expounded on the roles of the civil society. According to Keane, civil society has two main functions: precautionary against the State to balance, reconstruct and democratize it, and advocating, the expansion of liberty and equality in civil society itself.[2] In a similar vein, it has been pointed out that an increased role for civil society is seen as a way of assuring accountability through more efficient service delivery and of putting pressure on political rulers- thus creating “participation” and “empowerment” in terms of giving voice to people’s demand for influence and welfare.[3] According to Shils, the idea of civil society has three main components:

The first is a part of a society comprising a complex of autonomous institutions, economic, religious, intellectual and political, distinguishable from the family, the clan, the locality and the State. The second is a part of society possessing a particular complex of relationships between itself and the State and a distinctive set of institutions which safeguard the separation of the State and civil society and maintain effective ties between them. The third is a widespread pattern of refined civil manners.[4]

In African countries, as a result of the combination of a lot of factors, the State is increasingly incapable of maintaining law and order and providing for the welfare of citizens. As a result, great expectations are being placed on the civil society to promote participation, empowerment, transparency, accountability and good governance. As noted above, there is no agreement among scholars on the conceptualization of the term civil society. In this paper, we adopt Diamond’s conceptualization of civil society as “the realm of organized social life that is voluntary, self-generating, (largely) self-supporting, autonomous from the State”.[5] . Civil society therefore encompasses professional organizations, town development unions, trade unions, ethnic organizations, student associations e.t.c. In this conceptualization, civil society includes NGOs which are non-profit organizations formed by certain persons who have some vision and mission to pursue and elicit the support of others to pursue usually specific issues such as environment, human rights, women’s rights, democracy, development, debt, children’s rights, rights of the disabled e.t.c. In this conceptualisation, NGOs are a subset of civil society organizations. This is in tandem with the position of the UN which refers to “the accreditation and participation of civil society, including NGOs.”[6] But in this keynote address, we will use CSOs and NGOs interchangeably.

b. SOCIAL MOVEMENTS

Social movements are purposeful, organized groups that strive toward a common goal, such as creating change, resisting change, or giving voice to disenfranchised groups. Social movements typically emerge when there is dysfunction in the relationship between systems, systematic inequality, deprivation, or widespread discontent. Examples of social movement organizing include the anti-tobacco movement, the Arab Spring, the anti-apartheid movement, the workers' movement, the women's movement, and the student movement.

In the current era, social media plays a pivotal role in social movement mobilization, and artificial intelligence has great potential for enhancing this mobilization.

Several scholars have explored the reasons behind the birth, growth, and maturation of various types of social movements. The 1950s saw the emergence of significant social movements in the US and Europe, including the civil rights movement, the anti-Vietnam War movement, the feminist and gender equality movements, and the environmental movement. The theories explaining these phenomena include:

1. Deprivation Theory: Social movements arise when certain people or groups in a society feel deprived of specific goods, services, or resources.

2. Resource Mobilization Theory: When individuals in a society have certain grievances, they may mobilize necessary resources, such as money, labor, social status, knowledge, and the support of the media and political elite, to address these grievances.

3. Political Process Theory: This theory posits that the success of movements depends on the availability of political opportunities and the power of the government. If the government is strongly entrenched and repressive, a social movement is likely to fail. Conversely, if the government is weak or tolerant of dissent, the movement has a better chance of flourishing.

4. Structural Strain Theory: This theory suggests that six factors are necessary for a social movement to grow:

1. People in society experience some type of problem (deprivation).

2. Recognition by people that this problem exists.

3. An ideology proposing a solution develops and spreads.

4. An event or events convert this nascent movement into a bona fide social movement.

5. The society (and its government) is open to change for the movement to be effective.

6. Mobilization of resources as the movement develops further.

5. New Social Movement Theories: These theories move away from the traditional Marxist framework, which analyzes collective action from an economic perspective, to focus on politics, ideology, and culture. They emphasize new definers of collective identity, such as ethnicity, gender, and sexuality.

Social movements produce learning in two ways: direct learning when people participate in movements, and indirect learning when people observe the operation of movements. Both types of learning are crucial as they can transform the behavior of people in society. Social movements influence how people, both participants and non-participants, interpret the world, potentially impelling them to take actions that result in social change.

c. DEMOCRACY

Historically, all over the world, there has been concern about what system of government will be good for people. Various systems have been experimented including autocracy, monarchy and democracy. But from experience, it has been recognized that democracy is the best form of government. Autocracy is characterized by one individual making all important decisions and oligarchy which puts the government in the hands of an elite is less desirable when compared to democracy.[7] Democracy is so important in the world today that it has become the driving force of development making many scholars draw a nexus between democracy and development.[8] Although different people emphasize different issues which they consider to be crucial to democracy, the majority of people agree that liberal democracy contains some basic principles which include citizen participation; equality; political tolerance; accountability; transparency; regular, free and fair elections, economic freedom; control of the abuse of power; bill of rights; accepting the result of elections; human rights; multi-party system and the rule of law. The idea of democracy is that the majority of citizens make the decisions on who governs and the policies, programmes and projects to be implemented for the benefit of the people. But the challenge especially for the working people is that it has been recognized that liberal democracy is facing a crisis of legitimacy and declining confidence in political leaders and institutions necessitating the need for democratic renewal through increasing citizen participation.[9] This has raised the issue of a more nuanced consideration of Socialist democracy.

3. STATE OF CIVIL SOCIETY, SOCIAL MOVEMENTS AND DEMOCRACY IN AFRICA

Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) play crucial roles in promoting democracy and development. During the colonial era, there were strong CSOs in Africa including religious organisations, trade unions and community associations. After independence, many African countries experienced military rule which tried to suppress civil society organisations. But there emerged a lot of CSOs fighting to end military rule. However, the democratisation wave of the late 20th Century led to the growth of CSOs advocating for human rights, constitutional and electoral reforms, protection of vulnerable groups and social justice.

Over the years, CSOs have contributed to the growth and development of Africa. Civil Society Organisations in Africa have historically contributed to promoting development through advocacy for social change, providing services, especially for underserved groups, fostering participatory development and holding the government to account. From grassroots organisations to large national organisations, CSOs contribute to various aspects of development in Africa including education, healthcare, governance, livelihood, rule of law, peace and conflict transformation, migration, human rights, environmental protection, social protection etc. It has been documented that CSOs in Nigeria for instance have played key roles in humanitarian assistance; influencing policy towards more pro-people legislation; reshaping the attitudes of traditional and cultural practices; improving the public awareness of human rights; and providing economic support for internally displaced persons and communities. [10] In addition, CSOs contributed to the attainment of independence and campaigning against military rule that led to the transition to civil rule in 1999. Moreover, CSOs in Nigeria are also an important provider of employment opportunities. In addition, CSOs in Nigeria contribute to harmony and stability in society by addressing normative issues that the Government and private sectors have neglected such as human rights, gender equality and women empowerment, social inclusion, credible, free and fair elections, vote buying, conservation, persons with disability, etc.

Despite the contribution of CSOs in Africa, they face a lot of challenges. There is constriction of the civic space. There is an upsurge in the arbitrary arrest of activists and restrictive CSO laws. In countries like Egypt, Ethiopia and Zimbabwe, there has been a crackdown on activists. In Nigeria, there have been repeated attempts to pass restrictive CSO/NGO bills which have so far been successfully resisted by the vigilance and mobilisation of CSOs. There is now a new attempt at CSO Self-regulation. There is also the challenge of funding and dependence on foreign donors. Although the spirit of Philanthropy is very high in Africa, it is yet to be organised in a way to support CSOs especially those involved in pushing for transparency, accountability and responsive governance. Related to the challenge of funding is the increasing professionalisation of civil society in Africa. In the 1980s and 1990s represented by Taju and Momoh, involvement in civil society was by choice to contribute to the transformation of Africa. But today, people target civil society to build a career in it. A lot of people now deliberately study NGO management, gender studies and development studies to work and build a career in the civil society sector. Combined with the need for funding, this has professionalised the sector and introduced market language into the sector. As we have argued elsewhere with Women in Nigeria (WIN) as Case Study:

With the flow of donor money to WIN and other NGOs, the focus of work changed from mobilizing membership dues and support to proposal writing. The method of work changed from demonstrations, rallies and picketing to holding of meetings and workshops in five-star hotels. The content of the struggle changed from an emphasis on social justice and gender equity to participation and affirmative action. The attitude of WINners and other civil society activists changed from sacrifice, comradeship and solidarity to opportunism and careerism. In the past, the major requirement for success and recognition in the civil society community was dedication, commitment and sacrifice. But today, it is the ability to write good proposals, report writing skills and workshop facilitation skills. Although some WINners will make the argument about continuity even with donor money, WIN has been conspicuously absent in popular struggles such as the struggle against unbridled neo-liberalism manifested in the incessant increase in petroleum prices in Nigeria resulting in a nationwide strike in July 2003 and an attempted strike in October 2003.[11]

In my view, the professionalisation of the sector in the modern world is not necessarily bad. The division between scholar and activist, politician and technocrat, and professional and revolutionary civil society activist can be at times fictional. You can be a Scholar-Activist like Taju and Momoh. You can be a politician and a technocrat; and a professional and revolutionary. There are leading CSOs in Africa such as CDD, CITAD, CISLAC, PLAC, Centre LSD, African Women’s Development and Communication Network (FEMNET), and Third World Network which can be both professional and revolutionary.

The history of Social Movements in Africa dates back to the colonial era where they led the struggle for independence.[12] They include the Mau Mau movement in Kenya, the National Liberation Front of Algeria, and the Mozambique Liberation Front (FRELIMO) of Mozambique. In the recent past, there has been movement-type organising such as:

a. The #EndSARS Movement began in 2017 against police brutality and extra-judicial killing by the Police in Nigeria.

b. #FeesMustFall in South was launched in 2015 and led by students against the proposed increase in university fees.

c. #Afriforum in South Africa was established in 2006 focusing on protecting the rights of Afrikaners in post-apartheid South Africa.

d. Y’en a Marre (Fed Up) in Senegal was formed in 2011 by a group of rappers and Journalists with a focus on political accountability and youth empowerment.

e. #ArewaMeToo in Nigeria which emerged in 2009 with a focus on sexual violence and harassment in Northern Nigeria.

All these movements achieved varying degrees of success. For instance, the #EndSARS and #FeesMustFall compelled the governments of Nigeria and South Africa to rethink policies and implement reforms. The #ArewaMeToo broke societal taboos forcing open discussion of sexual violence.

Democracy in Africa has experienced significant changes in the last three decades. The wave of independence in the 1960s led to the establishment of civilian governments. But by the 1970s, many of the countries were under military rule. The first direct military intervention in Africa leading to the overthrow of a civilian government took place in Sudan in November 1958 when General Ibrahim Abboud seized power. It took seven years before the second coup de tat took place on 19 June 1965 in Algeria after which there was a rapid succession of the military take over in Congo-Kinshasa (25 November 1965), Dahomey (22 December 1965), Central African Republic (1 January 1966), Upper Volta (4 January 1966), Nigeria (15 January 1966), Ghana ( 24 February 1966), Nigeria, again (29 July 1966), Burundi (28 November 1966), Togo (13 January 1967) and Sierra Leone (23 March, 1967). Since then, military intervention in politics in Africa has become a dominant feature. As a result, between 1960 and 1982, almost 90 per cent of the 45 independent Black African States experienced a military coup, an attempted coup or a plot; and during the course of some 115 legal government changes, the States experienced 52 successful coups, 56 attempted coups and 102 plots making military coup “the institutionalised mechanism for succession” in post-colonial Africa.[13] However, the third wave of democratisation in the late 1980s and 1990s marked another shift to civilian rule. Many countries in Africa have now institutionalised elections as a way of changing leadership for instance in Ghana, Senegal, Botswana and Nigeria. But in the recent past, there appears to be a democratic reversal with the military takeover in the West African countries of Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger.

Corruption remains a huge challenge with transparency International rating many African countries to be among the most corrupt in the world including Somalia, South Sudan, Equatorial Guinea, Libya, Sudan, Democratic Republic of Congo, Comoros, Chad, Burundi and Eritrea.[14] Perhaps, the greatest challenge is that since the return to civil rule, “democracy” in Africa has not translated to development.[15]

4. THE IMPERATIVE OF ACTIVISM AND RADICAL POLITICS IN AFRICA

Historically, Africa has faced numerous challenges from slavery to colonialism and neo-colonialism. Despite its rich natural and human resources, Africa is the poorest continent in the world. Nigeria for instance hosts the largest number of poor people in the world despite having a population of only 14 per cent of India and 15 percent of China. Nearly 40 per cent of the continent’s population live in extreme poverty surviving on less than $1.9 a day.[16] Over 20 per cent of children in Sub-Sahan Africa are out of school.[17] Africa is highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change despite contributing very little to global greenhouse gas emissions.[18]

In Nigeria, the crippled giant of Africa[19], the Poverty rate increased from 15 per cent in 1960 to 28.1 per cent in 1980 to 69.2 per cent in 1997 to about 40 per cent currently hosting the largest number of poor people in the world. It is instructive to note that by 2014, Nigeria ranked third in hosting the largest number of poor people in the world after India (first position) and China (second position).[20] But by 2018, Nigeria was declared as the world poverty capital with around 87 million people living in extreme poverty compared with India’s 73 million according to the World Poverty Clock. It is important to note that the population of Nigeria in 2018 was estimated to be about 195.9 million which is about 15 per cent of the population of India (1.353 billion) and 14 per cent of China (1.393 billion), yet it hosts the largest number of poor people in the world. The change was partly a result of social protection policies implemented by China and India combined with enlightened leadership and pressure from below. According to the McKinsey Global Report, 2018, China lifted 713 million people and India 170 million people out of poverty between 1990 and 2013. They achieved this feat through inclusive, pro-poor growth; fiscal policies for wealth redistribution; employment generation; public service provision and social protection.[21] Nigeria has poor development indices. Nigeria is ranked 163rd in the United Nations Human Development Index (HDI) out of 191 countries in 2021. Nigeria ranks among the worst seven performers in the World Bank Human Capital Index. Nigeria has the highest prevalence of severe malnutrition in Africa with about two million children affected. In 2022, Nigeria ranked 103rd out of 121 countries on the Global Hunger Index.[22] Nigeria's life expectancy is 52.7 years in 2021 (compared with 64.38 years in South Africa, 72.22 years in Egypt and 87.57 years in Japan). According to UNICEF, Nigeria has 18.5 million out-of-school children, the highest in the world.[23] In 2022, Nigeria ranked 16th out of 179 countries on the global fragile index. The World’s Economist Intelligence Unit report which ranks the best and worst cities to live in the world indicated that Lagos in Nigeria is the third worst city to live in the World.[24] The other cities are Damascus, Syria (1); Tripoli, Libya (2); Dhaka, Bangladesh (4); Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea (5); Algiers, Algeria (6); Karachi, Pakistan (6); Harare, Zimbabwe (8) and Doula, Cameroun (9). One of the key development challenges in Nigeria is the lack of inclusive growth. Rapid growth in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in the past did not translate into sufficient poverty reduction. From 2004 to 2014, Nigeria grew at an average rate of 8 per cent annually.[25] That is about 80 percent growth in one decade but poverty rates declined by only 10 percent points between 2004 and 2013.[26] This position was re-echoed by Muhammadu Buhari in his foreword to the Revised Draft National Social Protection Policy in 2021 when he stated that “Nigeria has not recorded significant progress in translating the impressive economic performance into improved well-being for the generality of Nigerians during the period of growth.” The reality was that inequality widened as the economic growth benefitted the rich more than it benefitted the poor.

Activism and radical politics have contributed to shaping democracy and development in Africa. The decolonisation of Africa is a testimony to the power of activism and radical politics. Leaders involved in the anti-colonial struggle like Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Julius Nyerere of Tanzania, Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe and Sam Nujoma of South West African Peoples’ Organisation (SWAPO)/Namibia harnessed radical ideologies to mobilise the masses against colonial rule. Post-independence struggles against dictatorship, corruption and military rule were led in many countries like South Africa and Nigeria by activists who subscribed to Marxist and Socialist ideologies.

The leaders of contemporary struggles in Africa against elite capture of the state, corruption, inequality, poverty and injustice come from different ideological backgrounds but are united in activism against the status quo. More than ever before, Africa today needs activism and radical politics.

5. LESSONS FROM THE LIVES OF TAJUDEEN ABDULRAHEEM AND ABUBAKAR MOMOH

There are great lessons to learn from the lives of the Late Tajudeen AbdulRaheem and the Late Abubakar Momoh. Both of them were Socialist ideologues, Scholars, Activists, Civil Society and Social Movement organisers and promoters of radical politics. Their contributions, the lives they touched and the people they mentored are still relevant in contemporary political discourse and continue to inspire a new generation of activists.

Tajudeen AbdulRaheem was born on 6th January, 1961 in Funtua, Katsina State, Nigeria. He studied political Science at Bayero University, Kano and later earned a doctorate degree from the University of Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar. Taju was a consistent advocate for Socialism and Pan-Africanism. He was the Secretary General of the Pan-African Movement where he championed the cause of African unity and the need for collective response by the African people. His work emphasized the importance of self-reliance, social justice and economic equity. Taju’s involvement in civil society was extensive. He was the Chairman of the International Governing Council (IGC) of the Centre for Democracy and Development (CDD). He was Deputy Director of the United Nations Millenium Campaign for Africa where he worked to promote the development of Africa. His efforts in civil society were characterised by a commitment to grassroots mobilisation and the empowerment of the people. Taju believed in the power of organising social movements to effect change. He was an ardent critic of neo-liberal policies that perpetuate inequality and underdevelopment. His clarion call was...Do not agonise...organise. Taju’s legacy is one of unwavering commitment to social justice and radical politics. His writings, speeches and organisational efforts continue to inspire activists who seek to change the system. His vision of a united self-reliant Africa and Pan-Africanism remains relevant in contemporary struggles for African unity against neo-colonialism and economic exploitation.

Abubakar Momoh was born on 21st April, 1963 in Auchi, Edo State, Nigeria. He pursued his higher education in Political Science earning a doctorate degree from the University of Lagos. He was Professor of Political Science and Dean of the Faculty of Social Sciences at the Lagos State University. Momoh was a prolific writer and thinker. His work focused on the intersection of politics, economics and society with particular emphasis on youth and social welfare. As a committed activist, Momoh was deeply involved in civil society organisations. He was a founding and leading member of many organisations including the Socialist Congress of Nigeria (SCON), Women in Nigeria (WIN), Civil Liberties Organisation (CLO), Committee for the Defence of Human Rights (CDHR), Campaign for Democracy (CD), Community Action for Popular Participation (CAPP) and Transition Monitoring Group (TMG). Momoh’s life and work remind us of the importance of intellectual rigour and grassroots activism in the struggle for a just world.

There are great lessons that we can learn from the lives of Taju and Momoh. They were both Socialist ideologues committed to Social Justice. Their lives teach us that ideology is important. We need to return to promoting Socialist ideology in our schools and movements. Secondly, both of them believed in the power of collective action and grassroots mobilisation. Their work and lives are highlighted for us to revisit our ways of civil society organising and movement building. Thirdly, they combined intellectual rigour with activism and practical work. This teaches us that the dichotomy between scholarship and activism can be fictional. Finally, Taju died on 25th May 2009 at the age of 48 years and Momoh died on 29th May 2017 at the age of 54 but we are here today celebrating them. This should teach us that life is temporary. It is like a stage. You play your part and depart. After that, you will only be remembered for what you have done.

6. CONCLUSIONS AND THE WAY FORWARD

It is clear to us that the development of society is not a linear progression. It is governed by the laws of dialectics. The struggle for and deepening of democracy is not a dash. It is a marathon. Africa has made progress. Africa is making progress in the midst of huge challenges. The lives of Taju and Momoh serve as inspiration for us to continue to deepen democracy in a way that it will deliver development.

Civil Society and Social Movements can play big roles in deepening democracy and bringing about development. To do this, civil society organising must improve. We must improve the capacity of civil society actors to act as professionals without losing revolutionary fervour. Civil society organising must bridge the gap between the scholar and the activist, politician and technocrat, and professional and revolutionary. The CDD will have a lot of role to play in this regard. In addition, civil society organising needs to change. Organising workshops and seminars in five-star hotels and issuing communiques are unlikely to shift the needle. There is a need for new ways of organising. Civil Society must conduct evidence-based policy research and use the evidence for advocacy. But more importantly, such reports must be used to mobilise citizens to demand transparency, accountability and responsive governance. This is why CSOs must promote, capacitate and work with Social Movements in Africa to bring about transformative change.

The deepening of democracy in Africa requires work at different levels. As noted above, civil society and social movements have roles to play. In addition, the way politics is played in Africa needs to change. We need to fix the politics dominated by “uncivil” people whose interest is looting and brigandage. The beginning point is that decent, hard-working and God-fearing professionals must participate in politics. It was Plato who counselled us that “if you refuse to participate in politics, you will be ruled by your inferiors.” Edmund Burke admonished us that for evil to triumph is for good men to do nothing. Frantz Fanon warned us that the future will not pity those men and women who possess the exceptional privilege of being able to speak the words of truth to their oppressors and have taken refuge in an attitude of passivity, of mute indifference and in some cases of cold complicity. Frantz Fanon argued that any bystander is either a coward or a traitor. It has to be recognised that the ruling class will never relinquish power on its own accord.[27] This will require the taking over of power by a coalition of patriots and democrats and the establishment of democratic institutions that will work in favour of the people.

Secondly, there is a need for a developmentalist coalition to pursue the deepening of democracy that will translate to development. As Omano Edigheji has argued, throughout history, the ideology of development nationalism has been a major impetus for national development, especially in late developers (such as China, Malaysia, Mauritius, South Korea and Singapore) that want to “catch up”.[28] For Nigeria, he argues that:

Among other things, this calls for the creation of a developmentalist coalition that is made up of a few political elites, the top echelon of the bureaucracy and the patriotic business elite. Given the diverse ethno-religious composition of Nigeria, efforts should be made to ensure that the developmental coalition comprises of people from various ethnic and religious groups. This could be the basis to build a truly united country, as a sure guarantee to overcoming the ethno-religious conflicts that have plagued the country. The developmental coalition should be an elite group united mainly by the need for Nigeria’s development, and consequently, they have to be highly nationalistic and patriotic. In light of this, transforming the structure of the Nigerian economy, and consequently, enhancing its productive capacity should constitute the primary objective of the developmentalist coalition. To this would require that the promotion of industrial development should be accorded a national priority. A first step in this regard will be the formulation of an industrial policy, which among other things will identify industries for government support with clear targets, including technological upgrading, adaption and innovation, job creation and export requirements.[29]

A patriotic nationalist developmentalist coalition with a shared vision for national development can counteract the elite capture that we are currently witnessing across Africa.

Thirdly, there is the need to develop transformative leaders, especially in the political arena. Leadership has been recognised as one of the most important variables that affect the performance of any organisation, institution or nation. Study after study, superior financial and organisational performance, as well as other forms of success, have been linked to leadership.[30] Scholars have opined that the success or failure of organisations and nations depends on leadership excellence and not managerial acumen.[31] It has been documented that the progress, development and fortunes of many nations are tied to the type and quality of the political leadership that they have had and continue to have.[32] In a survey of 1,767 experts across the world, 86 per cent of the respondents agreed that the world is facing a leadership crisis.[33] According to Myles Munroe, the world is filled with followers, supervisors and managers but very few leaders.[34] Chinua Achebe argued that “the trouble with Nigeria is simply and squarely a failure of leadership. There is nothing basically wrong with the Nigerian Character. There is nothing wrong with the Nigerian land or climate or water or air or anything else.”[35] But scholars have documented that scourges of bad leadership and signs of darkened mood are everywhere in Nigeria.[36] Despite the recognition that Leadership is crucial for the development of organisations and nations and that leaders can be trained, there are very few organisations, especially in Africa dedicated to grooming leaders.

Myles Munroe put it aptly:

There is leadership potential in every person. Despite this universal latent ability, very few individuals realise this power and fewer still have responded effectively to the call. As a result, our nations, societies and communities are suffering from an astounding leadership void.[37]

This is why all efforts must be stepped up to build strategic leadership for sustainable development in Africa.

Fourthly, there is the need to give more attention to strategy. It is well established that strategy is very crucial to the development and performance of any nation. Strategy occupies a central position in the focus and proper functioning of any country. This is because it is a plan that integrates the nation’s major goals, policies and actions into a cohesive whole. A well-formulated strategy should therefore help to marshal and allocate a state’s resources into a unique and viable posture based on its relative internal competencies and shortcomings and anticipated changes in the environment. Strategies help to create a sense of politics, purpose and priorities.[38] The development strategy of a country is a comprehensive policy document that identifies the priority areas of the country, the resources available in the country and how to harness the resources to bring about improvement in the lives of the citizens. It contains clear priorities, targets, programmes and strategies. The strategy of a country should draw some inspiration from international and national projections that will inspire the people to put up the effort. It has been shown that development can be accelerated if there is political will combined with good policy ideas which are then translated into nationally owned, nationally driven development strategies guided by good science, good economics and transparent accountable governance.[39] There is a need for African countries to give more attention to the development of strategies.

Fifthly, there is the need to promote appropriate development approaches for Africa. As Fantu Cheru has argued, what is needed in Africa today are more “common sense” approaches that open up new avenues for increased productivity, by laying conditions for development through improved governance, increased investment in education and infrastructure, and improved access of the poor to productive assets and information.[40]

Finally, Africans must learn how to organise to change society. Organising for change has its own strategies, tactics and dynamics. It does not come from a few workshops, few tweets and few demonstrations. It is not a dash. It is a marathon.

Africa is rich in human and material resources. Africa is already providing leadership in many areas. An African, Amina Mohammed, OFR is the Deputy Secretary General of the United Nations. An African, Dr. Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala is the Director General of the Word Trade Union. An African, Comrade Ayuba Wabba was the president of the International Confederation of Trade Unions from 2018 to 2022. An African, Dr. Osahon Enabulele is the immediate Past President of the World Medical Association. In all these leadership positions, they have done well. There are potentials and possibilities in Africa. Africa can rise again. The spirit of Taju and Momoh should inspire us. Africa will be great!

ENDNOTES

[1] Beckman, B., Hansson, E. and Sjogren, A. (Eds)

[2] Keane, J. (1988),

[3] Sjogren, A. (2001)

[4] Quoted in J. Ibrahim (2001)

[5] Diamond, L. (1994)

[6] Quoted in Grant, W. (2002)

[7] Janda, K, Berry, J. M. and Goldman, J (1999), The Challenge of Democracy

[8] Igbuzor, O. (2005), Perspectives on Democracy and Development. Lagos, Joe-Tolalu & Associates.

[9] Bentley, T. (2005), Everyday Democracy: Why we get the Politicians we deserve. London, Demos.

[10] Centre for Democracy and Development (CDD)(2021), Civil Society Organisations in Nigeria: Impact Assessment Study.

[11] Igbuzor, O (2007), Women in Nigeria (WIN), Donor Agencies and the Struggle for Gender Equity in Nigeria in Feminism or Male Feminism? The Lives and Times of Women in Nigeria (WIN). Edited by Ibrahim J. and Salihu, A. Centre for Research and Development, Kano and Politics of Development Group, Stockholm University.

[12] Mamdani, M (1996), Citizens and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism. Princeton University Press.

[13] Jenkins, J. C. and Kposowa, A. Cited in Gofwen, R. I. (1993), Politicization of the Nigerian Army: and its Implications for the Third Republic. Jos, Salama Press Ltd

[14] Transparency International (2023) Corruption Perception Index.

[15] Edigheji, Omano (2020), Nigeria: Democracy without Development-How to fix it. Abuja, Zeezi Oasis Leadership Inspiration Ltd.

[16] World Bank (2020), Poverty and Shared Prosperity.

[17] UNESCO (2020), United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organisation.

[18] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)(2020) Report

[19] Osaghae, E. Eghosa (1998), The Crippled Giant: Nigeria Since Independence. Indiana University Press.

[20] Jim Yong Kim (2014), Nigeria, third on World Poverty Index-World bank President in Vanguard 11th April, 2014.

[21] Nino-Zarazau, M. and Addison, T. (2012), Redefining Poverty in China and India. Japan, United Nations University.

[22] NESG (2023) Op Cit

[23] www.africanews.com 13th May, 2022 and Daily Trust, 25th Jan, 2022.

[24] The 9 Worst Cities to live in the World www.independent.co.uk

[25] World Bank (2016), Poverty Reduction in Nigeria in the last Decade. Page X.

[26] ibid

[27] O’ Malley, P. National Democratic Revolution

[28] Edigheji, Omano. This section is culled from the brochure of Nigeria Developmentalist Coalition informed by Dr. Omano Edigheji.

[29] Edigheji, O (2011), Building a Developmental State in Nigeria as a Transformative Development Strategy in Igbuzor, O (Ed), Alternative Development Strategy for Nigeria. Abuja, African Centre for Leadership, Strategy & Development.

[30] Fulmer, R. M and Bleak, J. L (2008), The Leadership Advantage: How the Best Companies are Developing their Talent to Pave the Way for Future Success. New York, Amacom.

[31] Sinek, Simon (2017), Leaders Eat Last. UK, Penguin Ramdom House.

[32] Igbuzor, O (2017), Leadership, Development and Change. Ibadan, Kraft Books Limited

[33] Petiglieri, Gianpiero (2014), There is no Shortage of Leaders. Havard Business Review December 15, 2014.

[34] Munroe, Myles (2009), Becoming a Leader. New Kessington, Whitaker House.

[35] Achebe, Chinua (1987), The Trouble with Nigeria.

[36] Anam-Ndu, Ekeng A. (1998), The Leadership Question in Nigeria: A Prescriptive Exploration. Lagos, Geo-Ken Associates.

[37] Munroe, Myles (1993), Beco0ming a Leader. New Kensington, Whitaker House.

[38] Patel, K. J. (2005), The Master Strategist: Power, Purpose and Principle. London, Hutchinson.

[39] United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) ( 2003), Millenium Development Goals: A Compact among Nations to end Human Poverty. Oxford University Press

[40] Cheru, F (2002), African Renaissance: Roadmaps to the Challenge of Globalisation. London, Zed Books.

RETURN

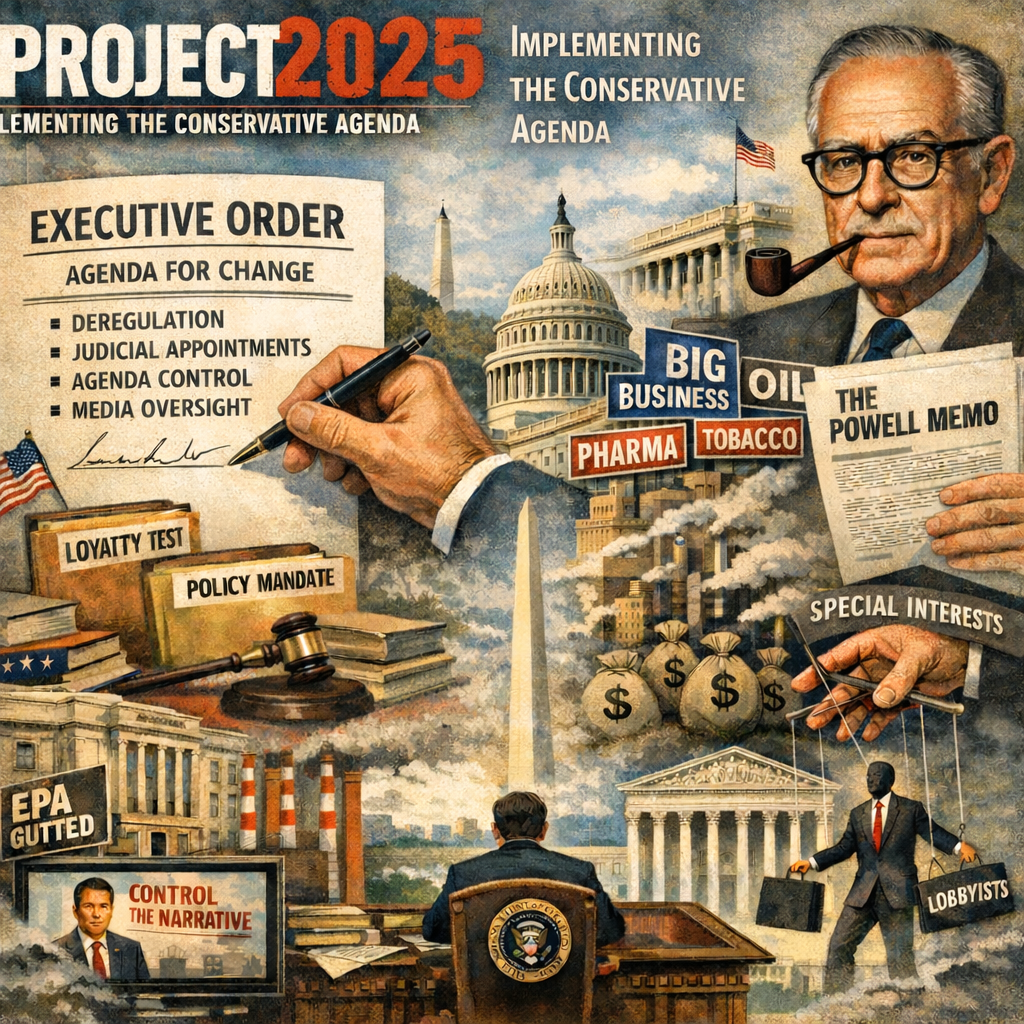

From the Powell Memo to Project 2025: How a 1971 Corporate Strategy Became a Global Template for Power In August 1971, a corporate lawyer named L...

The Market’s Mood Ring: How Volatility Across Assets Traces a Hidden Geometry of SentimentIf you want a fast, honest way to describe modern markets,...

Nigeria’s grid collapses are not ‘bad luck’ – They are a design failure, and we know how to fix themFirst published in VANGUARD on February 3,...

Islands of Credibility: Nigeria’s Best Reform Strategy Starts in the StatesFirst published in VANGUARD on January 31, 2026 https://www.vanguard...

Project 2025 Agenda and Healthcare in NigeriaThe US and Nigeria signed a five-year $5.1B Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on December 19, 2025, to bo...