Address by Dr. Chimaroke Nnamani, governor of Enugu State address to the Conference of Southern Governors. January 2001.

THE summit today and your presence here cannot be taken for granted. This is a great honour to me personally and great respect to my

people. Please, feel at home and enjoy Enugu's famed traditional hospitality.

Your presence here is not just a statement of your confidence and

commitment to the Conference of Southern Governors, it is a ringing

proclamation of the dire necessity for our summits to be held more

regularly as a platform for deliberating and resolving some pressing

national issues. Our maiden summit in Lagos, last October, has amply

advertised the positive potentials of the conference's role in

bringing stability to the polity.

I am convinced, as I believe your excellencies are, that the way

forward for Nigeria as a united entity is for us at various geo-

political levels to make a decision today, not tomorrow, that the

time has come for us as a people to forge our collective destiny in

the furnace of constant dialogue and frank discussions. This indeed

calls for us to rise up and speak frankly to ourselves and among

ourselves. I believe that it is through such cross-interactions,

horizontal and vertical, that we can expunge instability from our

body politic. If we talk about our collective and individual

problems, we are more likely to find solutions to them than when we

stay apart, throwing solo tantrums.

The failure of the political and constitutional engineering which

prepared Nigeria for independence from Clifford's in 1922 to

Lyttleton's first ever Federal Constitution in 1954, and the

subsequent constitutions imposed by the military is the denial of the

right of contribution to these documents to the people for whom the

contents are intended. The reality has been that the operation of one

document throws up the imperfections which sooner than later engender

fresh clamour for constitutional re-engineering. This is why at 40

years, Nigeria seems fixated on the problem of writing a workable

constitution. We have a responsibility as leaders and citizens of

this country to take constructive steps to put a halt to this

unwholesome trend.

If after the amalgamation of the Colony and Protectorate of Southern

Nigeria and the Protectorate of Northern Nigeria in 1914, there were

no constant clamour for reforms, there would have been no London

Constitutional Conference of 1953, and probably no Lagos Conference

the following year and no Lyttleton Constitution thereafter. There,

probably, would have been no independence for Nigeria today. And no

Federal Republic of Nigeria!

>From the divide and rule tactics of the colonial government, complete

with its disruptive force, Nigeria has remained a mere geographical

entity, bereft of any sense of collective nationalism. The differing

strategies of employing indirect rule in the three regions helped to

entrench ethnic and sectional jingoism above national cohesion. The

net result has been virulent protests and riots which have pervaded

the land. The Jos riots of 1945; the Kano riots of 1953; the Tiv

uprising of 1959-60 and 1964 and full blown violence in the West in

1962 were ample symptoms of these social tensions which were to

assume a frightening dimension with Major Nzeogwu's coup d'etat of

1966 and the civil war of 1967-70.

To stem this crisis, subsequent Nigerian leaders have embarked on

splitting the country into smaller units in the vain hope that the

problem will go away. From three regional structures, Nigeria moved

to four regions, and when the civil war broke out, to 12 states.

Further exercise by the Murtala/Obasanjo administration split the

country into 19 states in 1976. Ibrahim Babangida changed the

landscape to 21 and later 30 states, before Abacha increased the

tally to 36.

Rather than help to bring the tension down, the multiplication of

states has tended to stoke it because it helps to further strengthen

the already strong centre. In the process, it heightens the fear that

the centre is indeed excessively centralised in the same manner as

military chain of command, and therefore, unlikely to be able to

resolve the contradictions in the polity. The reason for this is not

difficult to find. In Nigeria's 40 years as a nation, democracy has

only worked for a collective period of 11 years. The remaining 29

years are military years, or the years the holocaust ate away, as the

popular saying goes.

The human rights wild fires which has continued to plague the Niger

Delta and the various forms of social tensions in Nigeria make

restructuring and its twin brother, resource control, compelling

imperatives in resolving the country's burning problems. As the

International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance

observed in its recent publication, Democracy in Nigeria: Continuing

Dialogue(s) for Nation-Building, Capacity-Building Series 10: "The

major basis on which the demand for restructuring has been made is

the relative autonomy of the component ethnic nationalities in

Nigeria". It is now left for us to determine the parameters for this

relative autonomy, considering that restructuring without resource

control is like building a house on a foundation of quick sand.

It must be noted, however, that there is a strength in Nigeria's

diversity. There is greatness in that rainbow coalition, a coalition

of languages, of tribe, of religious affiliations, ideologies, wants

and desires. All the same, there needs to be a true structure that

guarantees certain degree of autonomy, so each different group can

pursue its different agenda peculiar to it under the umbrella nation

Nigeria; call it true federalism or whatever. The periphery must be

strong, must be vibrant and cohesive. But the centre needs only to be

strong just enough to hold.

At the threshold of independence in 1959, some sections of the

country trembled over the stark implications of a federal structure

with a strong centre. There were obvious inclinations to strong

regions and a weak centre. The songs are different today. The

principle of each part maintaining its identity and contributing to

the centre according to the limits of its resources and ability as

the binding philosophy for the federating units have been jettisoned

over the years. So, what makes this option more compelling now than

it was over half a century ago?

The variables which made the conferences in London and Lagos

imperative nearly 50 years ago are still potent today. The national

question which provoked our nationalists to question the monopoly of

the colonial government over the bread and butter issues are still

rearing their ugly heads in the form of resource control and national

conference.

The clamour for resource control and its attendant demonstrations

have their roots in our colonial legacy. Having effectively

subjugated the Niger Delta between 1886 and 1889, the colonial

authorities sought to oust our people, especially the indigenous

population from the bread and butter issues in the economy of the

colony. With the 1914 Colonial Minerals Ordinance, which bestowed

monopoly on "British and British-allied capital," the colonial

masters excluded Nigerians from participation in the oil sector. In

the same manner, our indigenous representatives, when they became

gracious enough to appoint or elect them into the colonial

parliament, were excluded from issues pertaining to mining,

agriculture and resource control generally. To ensure total monopoly

in the economy, the flourishing trading kingdoms in the Niger Delta ñ

Opobo, Bonny, Brass and Aboh were subjugated. King Jaja of Opobo who

offered resistance paid with his life in exile in 1891.

Shell D'Arey and later Shell-BP became the sole prospector of oil in

Nigeria. Even as other multinational companies joined the oil

business, the marginalisation of the Niger Delta did not abate. The

feeling of marginalisation engendered by colonialism grew as the

devastation of the area worsened by the day, even as oil increasingly

played a leading role in the country's economy. As the degradation of

the environment in this area grew in inverse ratio to the area's

contribution to the national treasury, the flashpoints in the region

multiplied. The situation worsened when the Federal Government after

wrestling the control of these resources from the colonial

authorities went ahead to behave as if the student had surpassed the

master. The lack of openness and transparency in accounting for and

disturbing the resources of the country over the years and the

lopsidedness in siting social amenities procured from oil revenue

increased apprehension in many quarters that not only are some

animals more equal than others, the wolf may indeed have only

conveniently donned the skin of goat.

The highpoint was the mushrooming of various movements for the

betterment of the Niger Delta and the other parts of the country. The

Bill of Rights presented by the Movement for the Survival of Ogoni

People (MOSOP) to the Nigerian people and the United Nations in the

early 90s lamented that for the area's contribution of $30 billion to

the national till between 1958 and 1990, Ogoniland and by

extrapolation, the entire Niger Delta, had nothing to show for it ñ

no meaningful representation in Federal Government, no pipe borne

water, no electricity and no jobs. In the aftermath of this

presentation, the area became a theatre of war and degradation of the

people's right to free speech and association.

The position of the international community on the matter did not

deter the military authorities from executing nine Ogoni leaders in

1996. Neither did it stop the devastation of Odi in 1999, in the

aftermath of the Egbesu crisis in the area. Our duty as leaders is to

manage this Niger Delta question in a manner that will bring

permanent solution to the problem. According to the International

Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance in the same report

cited earlier: "Resource control is, perhaps, the central emerging

issue in the Niger Delta. The general attitudes seems to be that

without restructuring the Nigerian society, economy and polity in the

direction of letting people control their resources, democracy in

Nigeria has little chance of succeeding". Can it now be said, in the

light of the above realities, that the present effort by the Federal

Government to tackle the problem through the Niger Delta Development

Commission will suffice? Otherwise, shall we fold our arms and allow

this democratic experiment founder once more?

In the days of the groundnut pyramids, cocoa and palm oil derivation

was fashionable, probably because some saw some perceived advantage

in resource distribution. Has someone stopped to ask why the regional

governments all over Nigeria were able to execute independent

political programmes without reference to the centre? The simple

answer lies in the autonomy which the regions enjoyed in generating

and husbanding revenue, and only remitting to the centre the royalty

necessary for operating the federal exclusive list. Why did the

military dump this derivation formula once oil started laying the

only golden egg in the economy?

What is the implication of this for national security? As we are

aware, security is intrinsically linked to the economy, in the same

manner that the economy is inextricably woven with politics and

administration. And as Lord Denning puts it, we cannot divorce

national security from natural justice. Of course, natural justice

implies equity and fairness. So, what are we saying here? National

security is not an abstract. It relates to people and issues. It

relates to the economy and it has its anchor point in justice. What

are the variables that nurture national security? How does a nation

begin to conduct its affairs in a manner that guarantees its security?

Neither can national security be treated in isolation from the

security of the component parts. The regions were strong because

before the emergence of the national police force the regions had

direct responsibility for such matters. The decisions of the alkali

courts in the North were enforced by the regional police while courts

marshals popularly known as courtman in the localities enforced the

judgments of Native Authority Courts in the East and the West. Even

the crisis of interference in local affairs by the federal police

reared its head as far back as the early 60s during S.L. Akintola's

political crisis with Chief Obafemi Awolowo. That the national police

force has not been sufficiently able to handle the issue of security

of lives and property is evidenced by the resurgence of state

controlled paramilitary forces in some states in Nigeria. In the

Second Republic, the tendency was manifested in the road marshals

created by governments controlled by the Unity Party of Nigeria (UPN)

in the West and the Nigerian Peoples Party (NPP) in the East and the

Middle-Belt.

The factors which made their emergence imperative in those days are

still germane today. The explosion in the number of militant

organisations across the country Oodua People's Congress (OPC),

Bakassi Boys, Arewa People's Congress (APC), Egbesu Boys, among so

many others, ñ is a clear manifestation of overbearing pressure on

the resources of the federal police and a big question mark on its

ability to effectively police the entire country in the face of its

limited resources and apparent shortage of manpower.

The implementation of the State Independent Electoral Commission, as

enshrined in Section 197(b) and elaborated in the Third Schedule,

Part II (B 3-4) of the 1999 Constitution is one step which can aid

the process of restructuring and political stability. It will

immediately bestow autonomy on the states with regards to internal

affairs. It will equally bring cohesion in the states because each

state chooses leaders who can deliver according to its local

peculiarities and political nuances. Its successful implementation

shall be a litmus test of the ability of the states to harness the

powers and resources being devolved to them, for the development of

their localities.

Besides, it will help to establish clearly the place of the local

government system in a truly restructured federation. It will help to

mobilise the local governments, to provide leadership in tandem with

the state governments, in that critical point of development, to

build a synergies that will help strengthen efforts to deliver

dividends of democracy to the people. Resources shall be

painstakingly generated and frugally utilised. It will spell the end

of the bazaar for those who have no programme for the people.

The emergence of the Sharia Legal System in some states in the North

and hoopla generated by the phenomenon in the country has refocused

the Sharia debate in the country. The failure of the 49 wise men who

drafted the 1979 Constitution to come to agreement on the Sharia

question almost marred the constitution drafting exercise. After walk-

outs and counter walk-outs, wise counsel prevailed and the survival

of Nigeria triumphed over the recriminations on Sharia. Sharia

remained in the penal code as a personal law. The sneaking of the

Sharia Legal System into the 1999 Constitution could not have been

done with the best of intentions. The volatility which attended the

news of the introduction of the Sharia legal system in Kaduna and

other states in the North speak of how much of a bad augury it is for

the country's political health. And so, did the deaths and

destruction of property, which followed in the wake of the crises.

Realising how insidious and dangerous religious insecurity is to a

country, the National Council of States intervened, advising for a

return to the status quo, which does not seem to have been fully

accepted. We have heard arguments about introducing cannon law as an

answer to the Sharia option. As leaders, committed to the

inviolability of the Nigerian sovereignty, we should avoid actions

capable of plunging the nation into chaos.

We must also, your excellencies, refocus our educational pursuit.

( See Communique released at the end of the conference)

RETURN

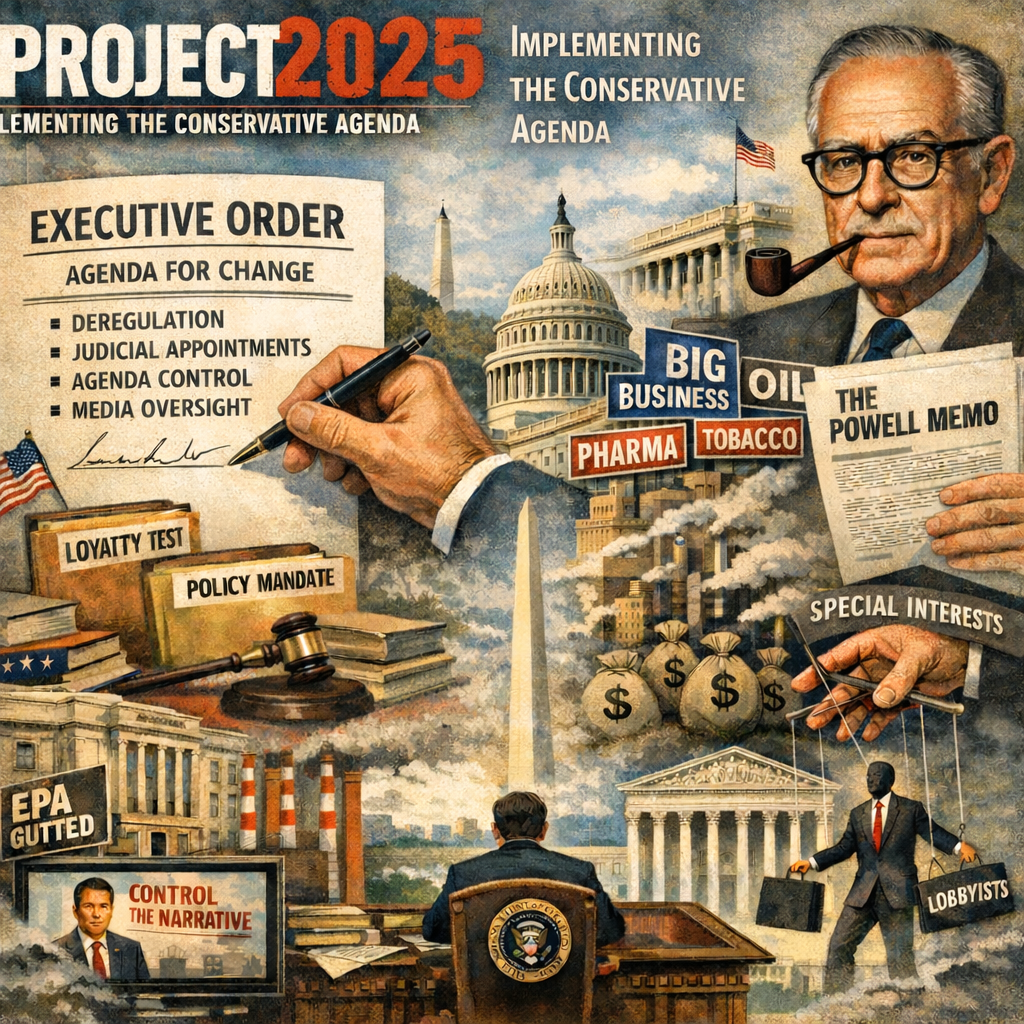

From the Powell Memo to Project 2025: How a 1971 Corporate Strategy Became a Global Template for Power In August 1971, a corporate lawyer named L...

The Market’s Mood Ring: How Volatility Across Assets Traces a Hidden Geometry of SentimentIf you want a fast, honest way to describe modern markets,...

Nigeria’s grid collapses are not ‘bad luck’ – They are a design failure, and we know how to fix themFirst published in VANGUARD on February 3,...

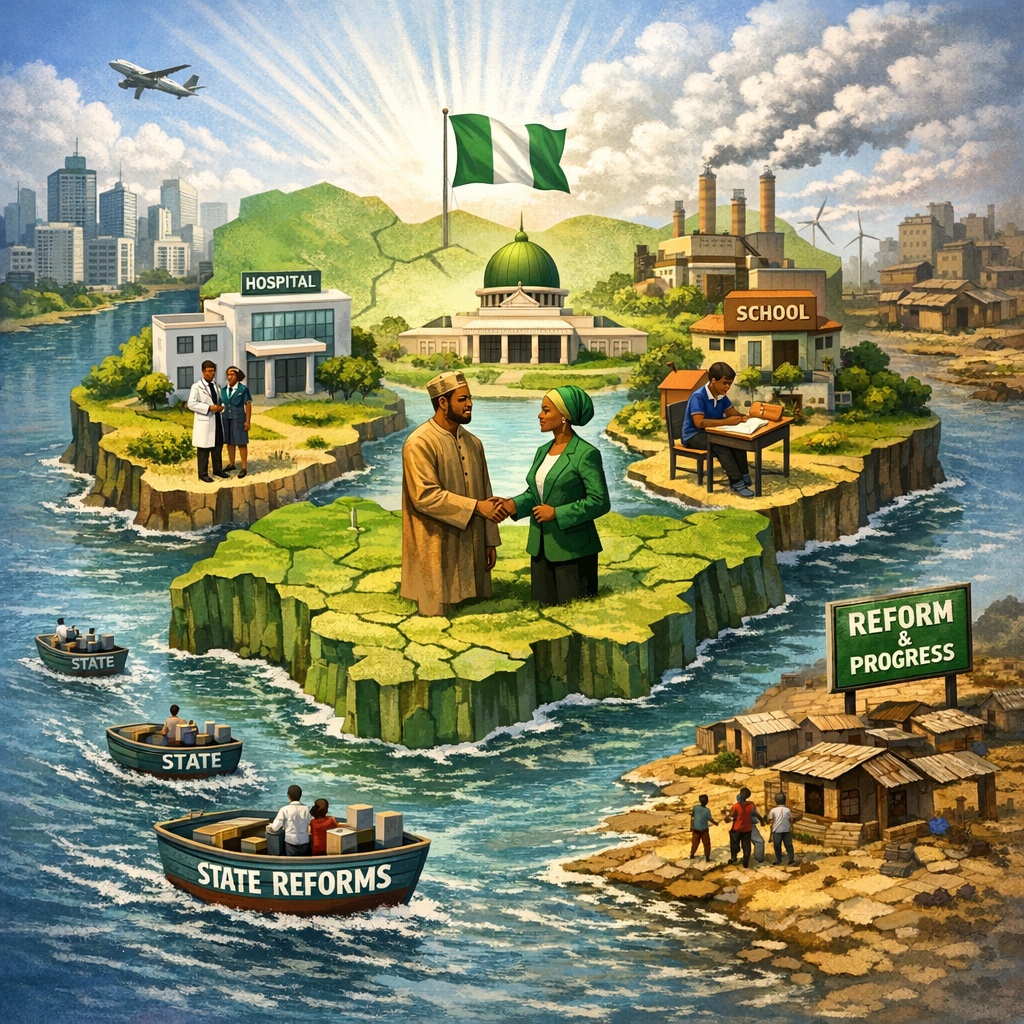

Islands of Credibility: Nigeria’s Best Reform Strategy Starts in the StatesFirst published in VANGUARD on January 31, 2026 https://www.vanguard...

Project 2025 Agenda and Healthcare in NigeriaThe US and Nigeria signed a five-year $5.1B Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on December 19, 2025, to bo...