THE LECTURE

The lure of Lokoja is like the appeal to the most pleasurable. I could not hide my fascination, when the team of the NUJ executive visited Enugu three weeks ago asking for my participation in their public function culminating in this lecture.

Indeed, Lokoja should hold the greatest attraction for every Nigerian. First, it is a scenic junction town, which will play great roles in the emerging socio-economic and political Nigeria. Second, it is a sprawling hilly town upon which peace and the air of contentment leave more prodding for greater interest and attraction.

Third, Lokoja, above all is a pronounced historical town, which has played the greatest of roles in the forming of modern Nigeria. Indeed, I cannot but be humbled by the reality of the great bones and ideas, which rested here, and which in may cases formed the foundation for modern Nigeria.

My entry into the Glass House, Government House, Lokoja, is in itself a departure point for my personal celebration of the great promises of the rising profile of our great country, Nigeria.

I consider it an unmatchable honour to be offered this podium even at the glare of a tough challenge as in tackling your curious topic, Gap Crisis in Transition democracy and the challenges of a proper expectation framework.

It is not yet clear to me why the journalists in Kogi State would wish me to specifically deal with this heady topic when in reality I do not consider myself as any reasonable plank of the great job of agenda setting, which sometimes is exclusively set for the men of the pen profession. In a way, I had ample reason to guess that their choice of my person may have roots in earlier positions particularly ones concerning the challenge of a more enlightened and committed media.

However, I thank the leadership of the Council for the honour in picking me, which has now qualified me to do business, even if briefly, in the glorious ancient city of Lokoja.

Initially, as I said elsewhere, the greatest threat posed to the prevailing democratic practice may not be entirely the evident squabble for power and the politicization of the entire civil society by the self seeking political elite, but more likely the fact that the system is currently undermined by the wrong expectation framework shaped at the dawn, as well as the course of the new era.

I had argued, although by way of a mere mention, that much as the given attitude of agitation and rowdiness of the political class did get the national political system too heated in the last 20 months, the consequent failure of the ruling wing of the elite to thwart a manipulation of the expectation framework posed a greater danger to the democratic practice than the entire shenanigans of the strewn of flashes-in-the-pan political players.

Initially, I assumed that the leading elements of the ruling elite would tackle this with proper contextualisation of the development programmes of government. This assumption was deduced from the initial indication of efforts to situate the gap between actual national

infrastructural developments, which had virtually halted in the last months of 1992 and the resumption of planning and implementation of national economic programmes.

In fact, I cannot pretend that I did not have some slight worries that the ruling elite would fail to appreciate the deliberate conditioning of the expectation values, the time-zone and the entire framework, for reasons not too far to ascertain. We are also aware that it is canvassed that the consequences of negation or the eruption of what is called gap-crisis as currently alleged by the populace had their roots in promises prior to the take off of democratic practice.

Values of appreciation, we know, were not set at any agreed event or process. Rather, what we have emerged from valid presumptions flowing from perceptions formed in interpretation of more global trends. In the case of time zone, it has been taken for granted that the attendant cumulative failure of the national system due to global economic trend and mismanagement could determine the specific periods for reverting to the good path so as to respond to the immediate and secondary needs of the citizenry.

No less trickier in this frame is the matter of overall framework which has been located in Burtons' transition gap-crisis of which the cumulative expectations of the citizenry were sooner than later blown away due mainly to the failure of the predecessor regime to state sincerely the limitations of the system at transition, just the same manner the successor group feasted on bloating the regenerative capacity of its cadres so as to earn the following of the people.

As often the problem in recent cases, the tendency to marry the varying posturing of the different groups - one moving out, the other moving in - only reveals the complication of matters and indeed, a bedazzling, of the common herd who would hardly interprete the trends. (A case of "the new masters never to sleep on a bed" or is it "never to sleep on one with bed sheets")

Of course, it was only natural that the liberation fighters who swept away their personal comfort and confronted the imperial armada also sought to sweep the British suzerainty over Nigeria and so were not taking anything for granted. Actually, the selected breed of MCK Ajuluchukwu, Sa'ad Zungur, Aminu Kano, Ikenna Nzimiro, Kola Balogun, Abraham Adesanya, Mokwugo Okoye, Raji Abdallah and Bob Ogbuagu, among others, had set out, preferring to operate parameters, which appealed to the people. Most of these were to revive the people's interest in their history, their group pride and a proper appreciation of their racial values.

Unexpectedly, some of these bordered on high-sounding verses for greater hopefulness upon a new dawn. That way, the people's expectations were set high and the hopes for the approaching new regime plainly laid its plank of significance on magnifying the lower points of the departing order.

However, the cases with expectation framework are not limited to the failure of the departing regime on one hand and the posturing of the emerging order on another. Sometimes, it is grafted into the national ethos or such momentary items of national agenda as set by the weightier public opinion and the press. In some cases, it is formed on the basis of social and political mobilization built and lifted to the crescendo by the class of political agitators and their sponsors.

Considered from our immediate historical plain, the termination of the democratic government of the first republic by idealistic soldiers, for what the larger number had been made to believe, caused a disruption of the enterprise of nation building which in turn could only be revived and recommenced by a new, strong and all-encompassing democratic administration. Closely related to this was the nostalgia for promises of national rebirth, "proper" sovereignty and economic assertiveness, as propounded by the various pre-independence liberation fighters. To a very large extent, the failure of both the evidence of indigenous capabilities for statecraft and eventual transformation from the regime of colonial oppression to African free and prospering states extremely unsettled the citizenry and the terrain was set for exploitation in exchange for propaganda value by the forces, which benefited most from the toppling of the regimes.

In a way, it validated the position of Kwesi Brew who in his great poetry, "lest we should be the last," had captured vividly the trauma of a disappointment that had risen among the African citizenry upon the ascendance of their own men in leadership of their various countries:

Lest we should be the last,

To appear before you;

We left our corn in the barn,

And unprepared, we followed

The winding way to your hut.

Our children begged for water,

From the women bearing golden gourds,

On their heads,

And laughing on their way from the well;

But we did not stop,

Knowing that in your presence,

Our hunger would be banished,

And our thirst assuaged;

By the flowing milk of your word.

Now we have come to you,

And we are amazed to find

Those you have loved and respected,

Mock you to your face.

This poem simply raises the disappointment of an honest searcher baffled by the attitudes of those who profess to be religiously pious. It captures vividly our expectations that have been disastrously shattered. Expectations expressed in such well-worn and vague phrases - "the flowing milk of your words," but which unfortunately has turned out unfulfilled.

In fact, flowing from the elaborate theses of Samuel Harry Burton, Oliver Mendaell and Josef Manngner in Post Independence Africa, such vast promises of eldorado which were followed by a quick relapse into erstwhile castigated elite pastime of the domineering colonial masters, invariably were not in the frame of expectation on which the people collaborated in the full drive for transfer of power.

It was then a wonder, a massive wonder indeed, that the emerging elite in power, did not attempt to gauge the expectation framework and relate same with the prevailing values in the first five years or so after political independence. And much as we could say that it was not entirely for the ruling elite to seek to change the expectation framework to stay in power, a somewhat ambivalence which bordered on arrogance had savagely afflicted the expectation framework of the citizenry and so altered their allegiance to state and to government.

It is not for me to state here that the levity with which the regimes treated the matter under review brought about a failure in conceptualisation, contextualisation and indeed problematisation of the expectation framework, the consequences of which were the brutal reduction, if not abrupt, but absolute termination, of the life span of the various governments of the era.

Of course, it is pertinent here to state very clearly that for purposes of getting the records right, the colonial practice which was punitive and exclusive called for the kind of liberation struggles which were hefted on some wild claims in favour of the craved self administrations, if only to give a picture of better alternative to imperial governments in the native lands.

One of the main problems, however, was that the same liberation fighters, or the usurpers of power, after the battle was done, failed to appreciate the necessity to quickly tackle their wild claims, which in reality tended to be the greatest threat to the survival of their regimes as they were neither quickly realizable nor even tenable. Rather, they had strangely embarked on mimicking the same colonial overlords whom they had just ousted and had immediately earned the opprobrium of the common herd who never hesitated to transfer their allegiance to elements of the forcible of take-over governments.

It is not yet clear whether this failure on the part of the emerging post-independence leadership came of a poverty of conceptualisation and or contextualisation of the political process, which they partook of. What was indefensible, however, was the inability to even maintain a grip on the indices of social re-conditioning which served their interests as they drove the hard road to national liberation.

Many have mounted severe ideological allegations against these, simply on the claim that their kind was largely overwhelmed by the complexity of the modern administration, which they inherited, but it appeared that the real tragedy of the era was the failure of the leadership class to grasp the shifting nature of the uninformed society. Upon that, the common herd usually located in the downtown or rural areas were simply made to perceive the emerging leadership as depicting a vitiation of the promises of national birth and social cohesion.

But against the backdrop of Burrton's Crisis in Post-independence Africa it is not entirely difficult to appreciate the institutional failure of the regime, right through the institutions of colonial rule, to properly situate political cum developmental tendencies as would be gainfully appreciated by all.

In fact, as argued by Burton, the deliberately planned shoddy transfer of power which gave greater recognition to mediocrity rather than merit; against what obtained in Paris, Brussels, Lisbon and of course, London; only revealed a crafty transition which exploited the ignorance of the larger number, in isolation of what should have been the truly emerging ruling elite.

Using the case of Nigeria as a good example, it has been argued that, had the mainstream of liberation fighters clinched power, their hard-line stance against begging the colonial question, would have culminated in the pursuit of a post-colonial economic agenda which would have shortened the gap between the expectation framework and the slight delay in the fuller realization of the relationship between State and the citizenry.

While this argument on one hand presupposes that the loser-elements at the end of the liberation struggle would have presented better leadership, it however failed to appreciate that the factors inherent in transfer of power by dictatorial regimes as the colonial governments would actively square up against such tendencies posturing on the sidelines of renegade ideologies and even the then cultivated communist grandstanding.

To that effect, the real challenge of ascendance to power carried with it the weight of living up the middle course, upon which power was affordable, and in extension, riding the crest of popular will, upon which a truly nationalistic feeling could be built.

It was indeed a pity that Mokwugo Okoye, Sa'ad Zungur, Raji Abdallah, Aminu Kano, MCK Ajuluchukwu, Osita Agwuna, Kola Balogun, Bob Ogbuagu, Ikenna Nzimiro, Abraham Adesanya and the others who tore off the mask of colonial pretensions and showed the way, could not grab power, having worked the population and reached the right sensitization for liberation. The attendant negation of patriotic values by some loser-elements actually built the culture of falsifying the expectation framework, if only to discredit the emergent leadership.

Of course, it was not enough that these worked at presenting themselves as credible alternatives, it was indeed a reduction of the struggles to clinching political power, first as an end in itself and secondly, as an avenue to achieving some social prestige or tackling matters of pecuniary interest.

But while I personally hold that this was neither here nor there, the abilities of leadership at an era to deliver the goodies of the state to all would not, and indeed had never, taken care of the crisis of gap created as in well scripted programme to impose the agenda and values of the society as a way of building pressure or suborning opposition against the prevailing leadership class.

Much as we can say that these belonged to the formative years of modern political power play, the current situation leaves no much in doubt as to coming very close to the very noisy efforts of the press and the political class to wrest power from the military.

Nigerians had every reason, arising from the promises of the anti-military struggles, to believe that the State, the infrastructure base, factors in social relations, popular political participation and, of course, the economic situation of the country, would take a sudden swift, upper swing, which would in turn usher in a healthy society devoid of the nuances and foibles levied against the military.

I am aware that some, particularly of the higher leadership class, believe that immediate positive actions of government, which would touch directly on the lives of the people, could fill the gap and sustain a stable state system.

Whereas this may have been adequate as it was proactive, the converse of it, to me, remains that the extent of national mobilization through the mass media and some community-based organizations, particularly the human rights and other non-governmental organizations, would demand more than programme-and-project in a situation where contest for power and class struggles exploited the unreal but the plausible and make-belief.

In studying the classic transfer of power from the colonial regime to the native power players in Nigeria, it was revealed that in many apparent cases, what was at issue was not such tangible economic or social indices as could be expanded or bettered for the benefit of the downtrodden, but the cleverly masked interests of the political elite which ran the steam of down-town discontent and penchance for immediate vengeance against political leadership.

The immediate appeal of the elite to manipulate the elements of the poor class has its direct explanation in the context of political economy upon which it has been clearly established by Manngner (Political Rivalry…) that the obscuring of the infrastructure development effort of a particularly ruling group of the elite had more to do with attempts at deliberately undermining such group for the ascendance of the other.

Usually, the quarrel against this scenario whose reciprocal reality upon change of guard has never been limited to perceived unpatriotic actions, was mainly the strange laxity and or levity with which the particular ruling group exhibited its power in relation to the expectation framework and in the time under review.

Of course, it has never been attractive to set parameters for conducts in political opposition in a democratic government. However, studies have revealed that rather than position government and its exercise in governance against deliberately ruptured expectation framework in the period under inspection, such elite group in power sat back and applied instruments of repression instead of persuasion against the tactics of the opposition.

Indeed, I soon came to believe that the need has become over-riding this time to pursue an understanding as well as the practice of proper expectation framework for the democratic process.

In arriving at the point where I began to see the necessity for this, I took into consideration the positive role of conflicts in social organization, alongside a proper streamlining or conceptualizing of the gap-crisis inherent in our periodic, even if presumptive, transfer of power.

It cannot be lost to the larger number of Nigerians that the struggle for power, which rode on the wind of agitation against military rule, presented a situation of rivalry for which the expectations of the citizenry got shaped, if not bloated, against the decay arising from past neglects.

It is not too attractive to me to begin to re-examine the various gaps arising from periodic transfer of power such as the contest for, and eventual transfer, in the years between 1977 and 1983, 1986 - 1992 and 1998 - 1999 onwards. In each of the cases, the gap crisis, which was more pronounced in ruptures in the expectation framework, resulted in the failure of the systems due to the inexplicable failure of the ruling elite to support its claim to leadership and direction of the state.

To that effect, it is convenient to state that the struggle for power in the years 1984 - 1986 was within the military while the civilian elite first fought for recognition and eventual interest in the power situation from the era of expansion of debates and alternative opinion by the Ibrahim Babangida government.

My argument at this juncture does not suggest that the scenario of expectation framework did not play in the military era but I hold strongly to the argument that it was a political system, which largely excluded the civil society and eventually pursued its own attitude to social re-organisation.

In a way, what could be called the effective entry of the civil society or pseudo-political class, in partnership with the military, was by the quasi-socio-political and economic reform organisations between 1985 and 1992, which instituted the political bureau, Constituent Assembly, Constitution Drafting Committee, the circumscribed national and state assemblies and the like, which were continued in the era of General Sani Abacha as Constitutional Conference and others.

In that case, the expectation framework was like a given situation of military in governance of which the greater attraction was the ousting by the bolder political elite. Moreover, such various institutions of popular debates and dialogue by the military were indeed to serve as valves and gauges for the crisis, which might arise from gaps, of failed expectations.

Of course, the issue here is not the apparent propaganda value of such upstart programmes or projects of the government in power but the strength of such ventures at holding the beacon for the formulation or cultivation of the national expectation framework.

In my estimation, such institutions of perenial national discourses as the National Reconciliation Committee, Federal Character Commission, Committee for the Devolution of Powers and the like which the Abacha government pursued were institutions of the military which effectively diluted, if not entirely altered, the expectation framework and managed the fixation of national attention on just the direction of transfer of power.

Please, note that I am not unmindful of the derision of such programmes of the military as mere diversionary and begging the question. But since it is not the subject under review, the main drive of the discourse is on the creative capabilities at appreciating the gap, which results in crisis or erodes citizens' hope and allegiance to the State.

But much as we know this, it differs so strongly in the case of a civilian (indeed democratic) government whose entry was preceded by an elongated directory of redeemable promises for which democracy was noted elsewhere. Besides the pronounced boastfulness of the individual, which came along the many cases attendant upon national promises for the dawn of a new era, the gap crisis ensues mostly from the institutional promises put together through public perception of popular government as against dictatorial eras.

The crux of the matter, therefore, was not the individual promises or boastfulness for election into offices but the more global values of regeneration and rebirth as ought to be occasioned by the new era. Indeed, the mere pronouncement of democracy and the very well circulated

knowledge of the wonders of alternative viewpoints in economic development provided the sound footing for much to be desired and for more to be assumed to be promised.

Now, against the background of the failed transfer of power from colonial to indigenous leadership, what with the attendant conspiracy to undermine the immediate inheritors of power by the departing regime, the 1999 change of guard now appears fatally viewed in the physical sense rather than in the holistic appreciation deserving of a new beginning on a social terrain, ruptured as it were.

One easy temptation in tackling the expectation framework of the current era is to try to lampoon the military, which we had accused of stagnating the system. In doing that, we had insisted that the only way to explain the gap between promises and realization of the social dream was the deviation of the system caused by the quantum of rot in the past era.

In reality, I have never bought this argument, which I think was flawed because it was like consigning and considering the question of expectation framework only from the point of view of one group of the political elite which, when viewed in the entire dimensions, cannot even be exonerated on the long run.

I hold this view for two strong reasons. One is that, there has never been a completely (all) military government without civil input, while another is that some vestiges of the same military, as hinted above, though they were instituted arbitrarily, have sustained better platforms for the appreciation and tackling of matters in the expectation framework.

In now examining the expectation framework of the current era, it will be desirable to take a look at the trend of national stagnation, against which a new beginning was expected, but at the same time, for which revival citizens' insistence and confrontation is looming, not far ahead.

Basically and indeed generally, the craving of the greater number has been for the expansion of the infrastructure base of the nation and the extension of real economic well being to all.

Coincidentally, examining the national expectation against the level of fulfilment, Mr. President, Olusegun Obasanjo declared on a television interview, Sunday 24th of August, that it was not too difficult to ascertain the total elements of the gap crisis attendant upon the transition from the previous administration to the current government.

According to him, these ranged from peace to justice, equity, democracy, national cohesion, security, economic expansion, international recognition, progress, co-habitation and overall infrastructural development.

He further said that this must go with a prioritization of core issues in national progression such as stability of the state, unity of the country, political sensitization and multi-sectoral/cross-sectoral, planning, programming and development.

In extension, Mr. President also averred that new issues germane to and or militating against growth and development such as the HIV/AIDS, rural blight, urban squalor and such degenerating actions as deviancy and adult delinquency, had attracted much attention and concern that their eradication or control formed a part of the national expectation.

These, which must have formed the official attitude of government in dealing with matters of the gap in the social equalization process, certainly had their role in determining the overall policies of government in either tackling same or advancing on the track of preventing further deterioration.

Well, in the context of the now famed gap-crisis which had always engulfed nations and systems on the verge of a transfer of administration, what may matter most than the other is not the recognition of the factors inherent in tackling festering national disasters but on the well choreographed pattern of appreciation of the matters and the attendant moderation of the expectation framework.

Indeed, it may be difficult to get the citizenry to moderate their general expectation when all the while they had acquiesced to the emerging order on the basis of the same hope and promises. Somehow, a strong moral question may even ensue when it is finally tabled that the need to moderate, attenuate or postpone some elements of the national expectation must ride the tenability of programmes which prior to the inception of administration, were presented as realizably easy and given.

More threateningly, the gamut of elements of national expectation may become excessively politicized, with an alienated elite forming the backbone of political opposition.

Initially, it will hardly be seen as the threat it portends if such opposition is merely seen as squabbling for positions in government rather than upholding creative roles in the economy.

Of course, were it to be elsewhere in the advanced world, the pattern of contest for power and indeed, the clinching of such power, does not exclude other elements of the society from the mainstream economy. Attendant upon this is political opposition based on tenable projections for government inclusion in economic activities. Such, already described as variable sum game, presupposes that it never mattered on what divide of the national politics for any person or group to play active and rewarding role in the economy. What appeared practically overriding were the variables to economy, power and group interests which could never be so skewed in favour of just a sect and totally against the vast population of the citizenry.

The pattern here, and indeed any other third world political economy, suggests that it is a winner-takes-all show, which in turn raises opposition to government in power to the dangerous stake and devious crest of envy, strife, destructiveness and vengeance.

If at the moment we accede to the claim that most often, the more active political groupings, which sensitized to build the national expectation, hardly ever come to power, it now becomes imperative to ascertain why those who inherit or usurp power never really work at framing the national expectation to suit the current actions of government.

Again, I restate that I do not know whether it is a failure of conceptualization and or expectation. But what I have readily discovered is the need to explore the Brian Dresden thesis on national prioritization which, as he averred, never came out of settled, formal debate; but of conscionable education and re-education of which the national media, whatever that means, remained the most assured machinery for accomplishment.

According to Dresden, it could never have been the responsibilities of private media entrepreneurs to commit personal resources and energy into setting the priorities of the ruling elite for the discernible citizenry. It was also not a burden of the professionals in journalism to circumscribe their practice within what appeared to be the duty post of the ruling elite. Rather, it was an agenda of leadership to drive the programme of development for which it must expend energy, resources and time for eventual appreciation and acceptance by the citizenry.

It cannot be argued that leadership in the current regional and national dispensation has not tried to map the priorities for development. It is not even that the citizenry would not have gotten the inkling of what constituted the national agenda, so to say. And it is not that the pre-administration elements, in sensitization, are too far in ideological stand to the main body of the ruling elite.

If these were the case, it would be profitable to ask, what then has made it difficult to place the national agenda so as to form an appreciable framework upon which the argument of moderation, attenuation and postponement would be sustained?

The resolution of the questions, as identified by Dresden, tallies with Thomas Hobbes' angling of the moral duties in political and social actions. This position strengthens the claim that it is not a matter of personal interest or reward but the fact of it being for the general good and for the stability of the state. To that effect, the responsibility was placed on the national media, which in his estimation, possessed the requisite intervention muscle to condition, re-condition, aggregate and re-engineer the national expectation.

While we can say that the leadership in the various stages of government did try to prioritise the expectation framework, the situation of campaign for power in the last elections, attendant upon wild claims and promises, actually confused, if not bloated, the expectation of the citizenry. But even at that, it was not incumbent on the same leadership to pursue the unrealistic as the national media had, the responsibility to distil the claims and positions to frame the proper national (including state) expectations. Such failure of leadership was long indicted by a remarkable captain of industry, Bunmi Oni, who declared in early 2001 that political leadership should try to fit the national expectation with the realizable elements of the economy so as not to fall prey to wild claims of capabilities and lure of white elephant projects.

To that effect, he posited that Nigeria was "like a nation devastated by earthquake. It takes time to clear the rubbles, first. Until that is done, no reconstruction should be embarked upon." Oni went further to admonish: "what this administration should do is to concentrate on clearing the rubbles and leave the building to other subsequent administrations."

It is not for me to prove that politicians, particularly those who would try to stage a comeback, would be content with clearing the rubbles and showcasing such as their ticket to return to power. But as I appreciate the scenario of proper recommencement as pursued by Oni,

I did notice that what the seasoned industrialist missed was that such altruistic endeavour as clearing rubbles and leaving tangible development to subsequent administrations, demanded such moral force and the explanation of the entire dimensions by the mass media.

In other words, the politician who would pursue a clearing-the-rubbles enterprise would have ignored the "lure of white elephants" and such other tangibles as state projects for which every politician would want to be remembered for.

Particularly, in the event that the media agenda always consolidates the position of the apparent, the noticeable, the tradition of immediate reward and glory of the ephemeral, politicians are always walking the tight rope of seeking out that which is easily noticed and for which a reckoning for future participation in politics could be assured.

That dilemma of the politician, in many cases, ought to be melted into the national expectation framework if clearly and obligatorily worked out by the national media. But unfortunately, however, the media have rather worked at hoisting the flag of such vitiating factors, which had festered the position of the elite opposed to government.

I am not in any way canvassing an obscuring of the views and stand of the opposition. I am neither claiming that government or elements close to it had the exclusive preserve of the knowledge of what should constitute the expectation framework.

What I argue is that it appears that there is the likelihood of the media ignoring the requirements for fulfilling the national moral obligation ahead of the more personal pecuniary demands.

When that is the case, what may appear as the dominant pursuit of the people, if not the agenda of government, would result in collision of causes and conflict in the system. This, in turn, when fully exploited by the elements of the vengeful opposition mentioned earlier, will certainly herald national instability.

My personal worries for this scenario are not that dissension or refined opposition may bring about distraction but that the seemingly unstreamlined national expectation would form the fishing ground for troublemakers. More so, the abundance of unresolved sectional, sectoral and cohabitational questions will be furthered and propounded as germinating from the presumed inherent distortion and incapability within the body of elite in government.

Again, I will refer you to recent television interview of Mr. President to buttress this point. Questions were raised on the internecine war in Warri and the seeming unresolved matters of petroleum pump head.

Of course, he did not take on this as analyzing the national expectation framework but the revelations of the statesmanlike answers pointed to a national dilemma of which much progress would hardly be made if the more demanding dimensions were not brought side by side.

In the case of Warri, there are strong aboriginal questions; genuine political agitations such as demand for more local government areas, inflamed bigotry and even a baffling zealotry among erstwhile cousins and friends.

In the petroleum pricing case, the questions are: Is it really a matter of price or pump head? Is it national security? Is it efficiency? Is it the so-called unreciprocated charity across our borders? And is it a matter of pipeline vandalisation and wastages?

I will not attempt to provide the answers to these questions because, indeed, they form strong planks of the national question, which, if we had a persisting media culture, would have gone half way in being resolved. I am rather attracted by what appears to be this culture or carnival of feeding frenzy, siege mentality and lynch mob inclination of major players in the media of mass communication.

I will not join the Jimmy Carter of 1980 to declare as the statesman did in his trying times, to "minimize as severely as possible (your) presence and activities in Iran." Rather, I will hold on to my position, as I previously argued, that, I am indeed drawn in by the redeemer's commitment of the media which in many cases borders on messianic selflessness.

I give full recognition to the claim that vibrant national media as we have were desired for some knocks and pricking for an erstwhile pampered ruling elite. But even at that, it is a wonder to me that the efforts of the same media appear to be limited to overstating national misadventures and periodic misconduct of members of the ruling elite.

In other words, the greater attraction to the media in this frame is not the means but the end and for which a shortfall is enough to elicit the derision or pummeling of an idle political opposition, all to the praise-singing of the media.

In a way, one had been strongly tempted to begin to ask, "is this sadism or ignorance or wrong orientation?" Somehow, it was assumed that all could be factors in this trend, which negates the agenda role of the media but celebrates emergent disruptions and or misadventures.

I have no doubt that this may change with time, particularly with the rising profile of the national readership and audience. It is on this hope that the matters in the gap-crisis can be resolved.

Somehow, I personally feel that the crisis of gap is created for the media and to be responsibly filled by the media. Somehow also, I feel that the national media have not appreciated this and so will continue to blow the chances of situating the factors at development and national progression.

I drew my conclusion thus: Whereas the disparity of national purpose arose from the seizure of power by the favoured players in the national liberation struggles; whereas the major players in the struggle against military leadership could not clinch power due mainly to their lack of national character and, whereas the global values of democracy assume rapid development and promotion of general well being, even paces far ahead of resources of state, such gaps that are created in the course of transitions should be assumed as inevitable and for which patriotic approaches should be the yardstick for both the reporter, opinion leader and elements of political opposition.

To that effect, your topic challenges of expectation framework in a transition democracy, has provided the beacon for articulation of that which has militated against the state and citizen, a sound opportunity for which we say, as in Enugu State,

To God Be The Glory.

RETURN

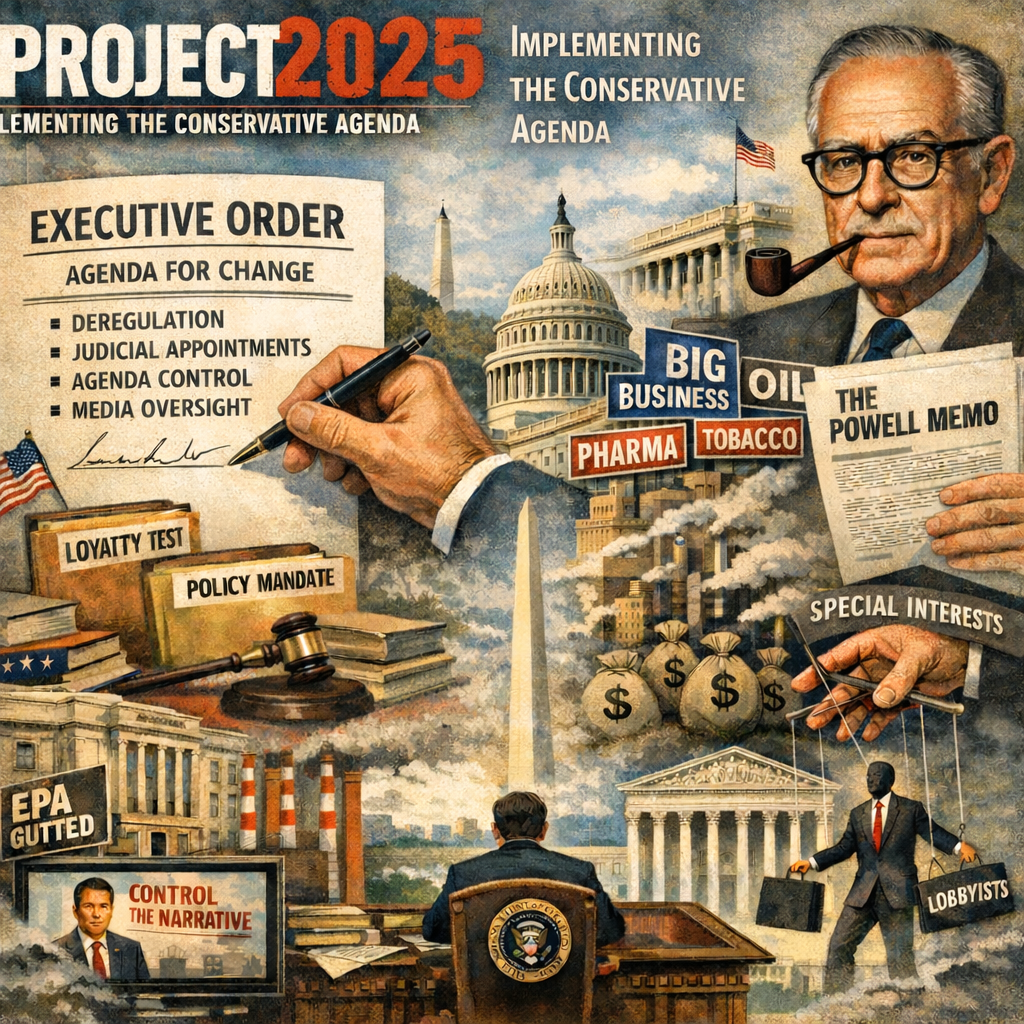

From the Powell Memo to Project 2025: How a 1971 Corporate Strategy Became a Global Template for Power In August 1971, a corporate lawyer named L...

The Market’s Mood Ring: How Volatility Across Assets Traces a Hidden Geometry of SentimentIf you want a fast, honest way to describe modern markets,...

Nigeria’s grid collapses are not ‘bad luck’ – They are a design failure, and we know how to fix themFirst published in VANGUARD on February 3,...

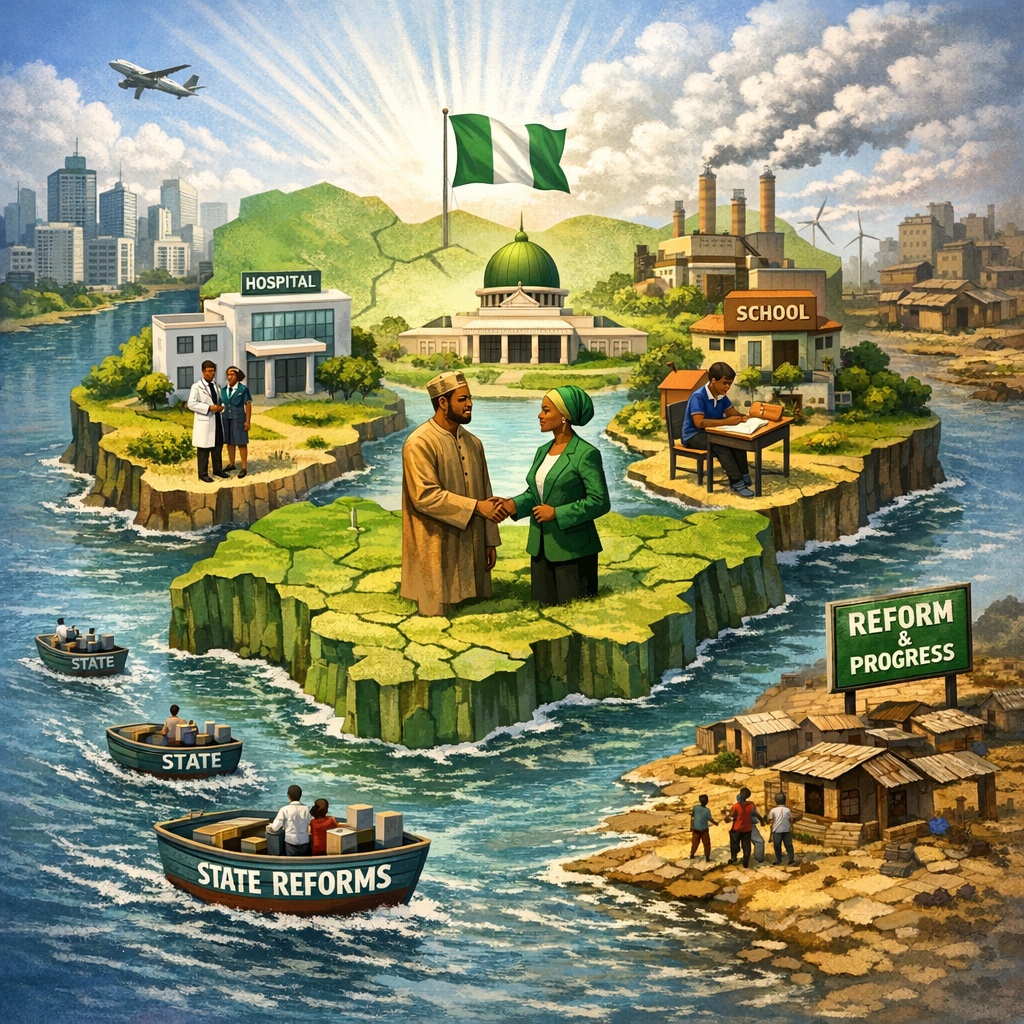

Islands of Credibility: Nigeria’s Best Reform Strategy Starts in the StatesFirst published in VANGUARD on January 31, 2026 https://www.vanguard...

Project 2025 Agenda and Healthcare in NigeriaThe US and Nigeria signed a five-year $5.1B Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on December 19, 2025, to bo...