Preamble

What is needed to achieve the MDGs in Africa: ‘scaled-up’ development or a different kind of development?

The answer is both. Clearly, current efforts to eradicate poverty are not working. With only 3500 days to go until the MDG deadline expires on December 31, 2015, still only half of African children complete primary school, and only 1 in 5 of Africans needing treatment for HIV/AIDS to receive it. The number of hungry people across the continent is increasing, and extreme poverty is actually on the increase.

The new aid pledged by the G8 and EU member states last year, combined with expanded debt relief and increased budgetary allocations from governments, could provide enough resources to solve all of these problems and more. However, unlocking the potential of this money will demand a radical overhaul of current development partnerships. In fact, without such reforms, as much as half of the $110 per African potentially available from the G8 pledge and from government budgets may be wasted.

Meanwhile, development must be seen in a holistic and integrated manner addressing issues beyond education and health to include issues of hunger, fair trade, water and sanitation and women empowerment.

Our research shows that:

· Only 50% of current aid is ‘real’ aid available for spending on schools, clinics, medicines and other essential MDG needs.

· Donor spending on consultants, research and training absorbs roughly a quarter of total aid flows, yet this “Technical Assistance” is widely acknowledged to be overpriced and ineffective.

· Over 20% of aid to Africa is tied. Primary education for every child in Africa could be funded simply from the savings from untying aid, which the OECD estimates would unlock an extra $7bn per year.

· Despite the overwhelming need for teachers, nurses and other public sector workers, much aid is too short-term and unpredictable to enable governments to meet these needs.

· Overly restrictive ceilings on public spending, requested by the IMF, also stop countries using aid to fund core MDG needs. Nations such as Uganda and Bolivia, for example, have been offered additional aid for education, yet have turned it down in part due to IMF pressure, as well as concerns about lack of long-term predictability of aid flows. In Kenya, IMF-imposed caps on the national budget have prevented the Ministry of Education from hiring the 60,000 teachers that it needs to expand primary schooling.

In addition, despite the G8’s pledge that African countries must be free to design and sequence their own economic policies, donors continue to use aid to push ‘one-size-fits-all’ policy prescriptions – such as water privatisation or export-led agricultural development. This happens both through individual countries’ aid programmes, and through loans from the IMF and World Bank, whose boards are dominated by the G8 countries. Most of these policies have failed to produce the sustained growth they were supposed to, many have carried unacceptably high political costs, and in some cases they have actually worsened poverty.

Donor conditions also choke the growth of democracy in Africa, forcing governments to render account to foreign bureaucrats rather than to their own people, and giving greater weight to the views of donor experts than the needs and aspirations of the poor themselves in formulating policy.

Finally, failure to fully write off the unpayable and odious debt of all poor countries means that much of what comes in as aid goes back out in debt servicing. Every day, Africa spends $30 million servicing its debt – enough to provide antiretroviral therapy for a whole year to every African who needs it. Before Gleneagles, two thirds of the countries that had actually received debt cancellation under HIPC were still spending more on repaying loans than on healthcare. Because debt relief has been tied to a highly subjective IMF judgment about whether countries are on track in fulfilling a slew of externally imposed economic benchmarks, the continuing debt overhang also stops countries determining their own paths to increase growth and achieve the MDGs.

Recommendations to donors and IFIs

Successful ‘scaling up’ of MDG investment demands that donor countries and international financial institutions stop using aid to drive policy choices that should be made in dialogue with citizens. Externally imposed conditions need to be ended, in order for strong downward accountability of governments to their people to take root.

IMF ceilings on public expenditure, including wages, must be lifted to enable greater investment in health, education and other priorities.

Donors must untie all aid, including food aid and technical assistance, and actively promote local procurement from African firms and organisations.

The Gleneagles multilateral debt reduction initiative must be expanded to all African countries and must be de-linked from external conditionalities. Donors should give new money to finance debt cancellation, and stop double-counting debt relief as aid.

Pushing these changes through will require more than the good will of donor countries. Voting power on the World Bank and IMF boards must be redistributed to give African countries a fair say in decisions that fundamentally affect their people. Currently, all of the countries of sub-Saharan Africa combined command less than 5% of the total votes at the IMF, while the US controls 17% of the vote.

Recommendations to African governments

Establish transparent processes that subject all new government borrowing, including agreements with the IFIs, to proper debate and scrutiny by parliament and civil society.

Assert leadership in relationships with foreign donors, and stop accepting aid that is not aligned with their priorities, comes with unacceptable strings attached or is tied to the purchase of unwanted goods and services. Propose robust mechanisms at a country level by which governments and civil society can monitor and hold donors accountable for their performance, as well as vice versa.

Meet existing regional and international pledges to align budgetary priorities with MDG commitments and national poverty reduction goals, such as the Abuja pledge to allocate at least 15% of government spending to health and the World Food Summit commitment to dedicate 10% of the budget to rural development.

Create the enabling conditions within which citizens will have the ability to hold their governments meaningfully to account for effective use of all resources, whether domestically generated or obtained from aid and debt relief. These conditions include freedom of information, freedom of association and building open spaces for debate in the press, civil society and local government, within which independent scrutiny of government actions is not only tolerated but encouraged.

This Statement was issued after a meeting held at Top Rank Hotel Abuja on 20th May, 2006 and endorsed by the following organisations:

ActionAid International

Women Aid Collective

Centre for Population and Development Activities (CEDPA)

Civil Society Action Coalition on Education for All (CSACEFA)

Pro-Poor Governance Network

Civil Society Coalition on Poverty Eradication (CISCOPE)

West African Civil Society Forum (WACSOF)

RETURN

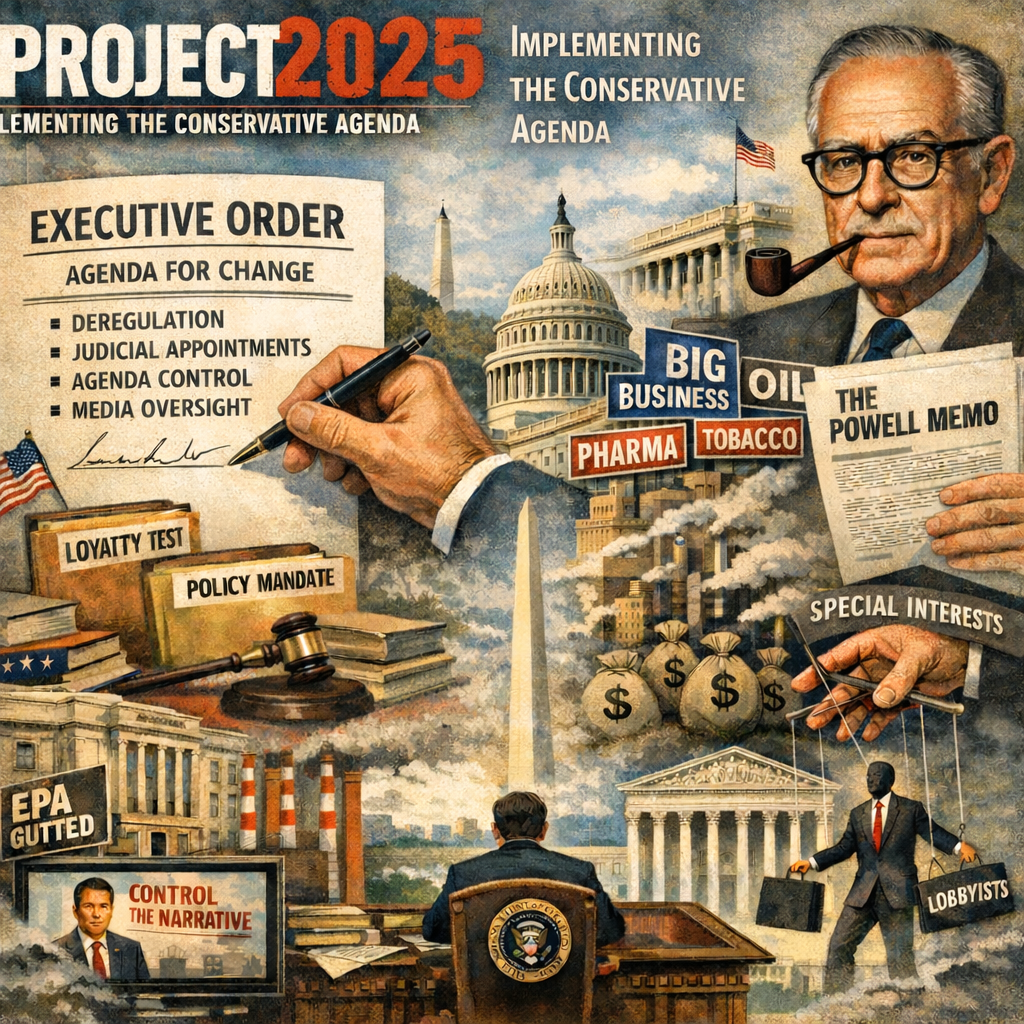

From the Powell Memo to Project 2025: How a 1971 Corporate Strategy Became a Global Template for Power In August 1971, a corporate lawyer named L...

The Market’s Mood Ring: How Volatility Across Assets Traces a Hidden Geometry of SentimentIf you want a fast, honest way to describe modern markets,...

Nigeria’s grid collapses are not ‘bad luck’ – They are a design failure, and we know how to fix themFirst published in VANGUARD on February 3,...

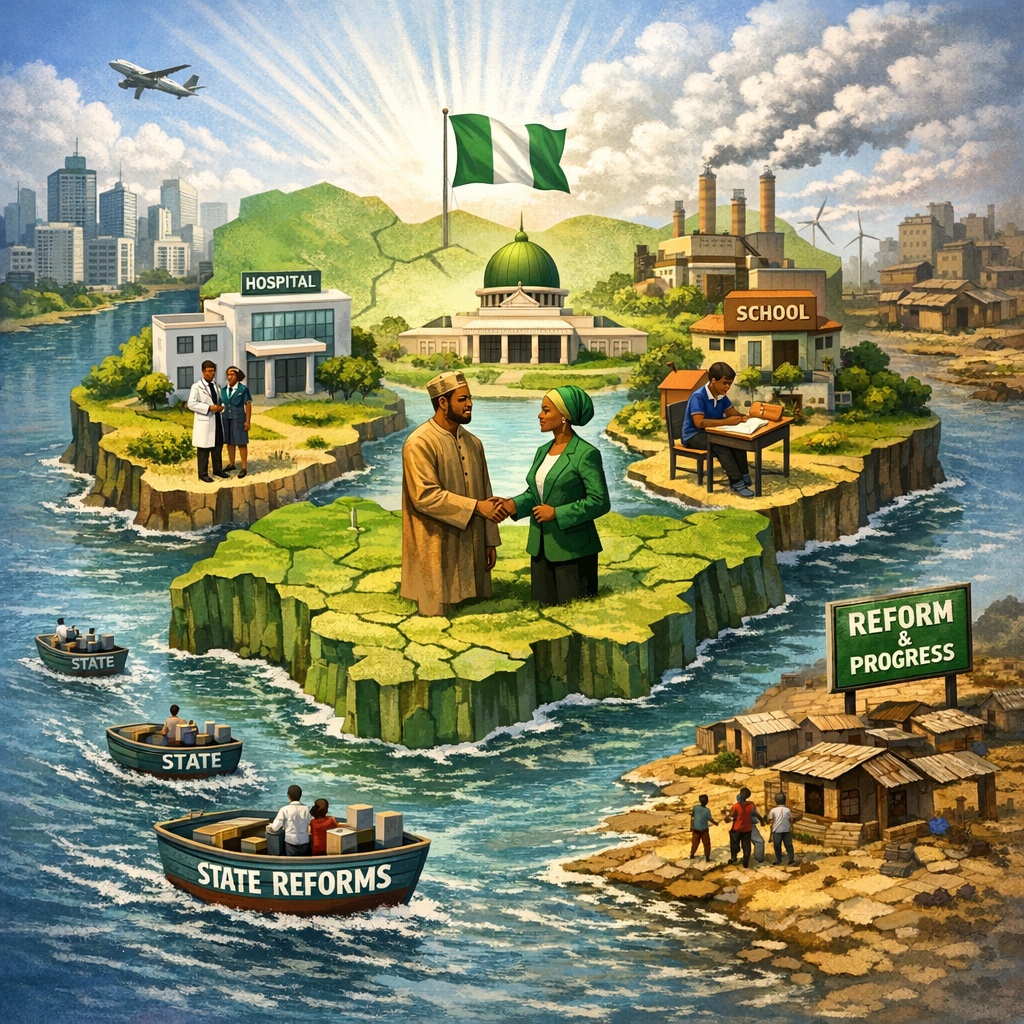

Islands of Credibility: Nigeria’s Best Reform Strategy Starts in the StatesFirst published in VANGUARD on January 31, 2026 https://www.vanguard...

Project 2025 Agenda and Healthcare in NigeriaThe US and Nigeria signed a five-year $5.1B Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on December 19, 2025, to bo...