culled from NEW AGE, November 08, 2005

There is a pain in the Igbo heart. There is confusion in the Igbo mind. There are excruciating aches in the Igbo body politic and society. The source of all that is the dilemma that faces every Igbo man and woman as he/she observes or participates in the affairs of contemporary Nigeria. There are varied explanations for the pain, for the confusion and for the aches.

Some ascribe them to the apparent disunity that seems to be a persistent but uninvited guest in any conclave of the Igbos since the end of the Biafran war. Some would rather lay the blame on the so-called marginalization of the Igbos. If you belong to the disunity school, then obviously the solution lies outside the Igbo context. If you, however, believe in the marginalization thesis, then obviously the solution lies outside the Igbos indeed in the Nigerian context given the skewed and irrational political and economic arrangements, which seem deliberately designed to offend and constrain the Igbos. The question really is: between disunity and marginalization, which is the cause and which is the effect? Or put another way, we seem to be in the chicken and egg situation. Perhaps, we need to start from the beginning or as our compatriot the revered Chinua Achebe would put it: we need to know where the rain started to beat us.

Igboland in historical perspective There is evidence that the Igbos have been in their present location in South East Nigeria for the last 5000 years. As I showed in the 1982 Ahiajoku lecture, the Igbo culture bears the imprint of the forest location where the culture developed, for example, in the rugged individualism, which is emblematic of the people. As the Igbo Ukwu bronzes attest by 968 A.D, the culture had blossomed into a sophisticated civilization whose genius is underscored by the fact that the quality of the Igbo Ukwu bronzes clearly better than the Benin and Ife bronzes that came along 500 years later.

It has been suggested that there is a 500-year hiatus or gap in the tapestry of Igbo history; this it has been speculated could have arisen as a result of an epidemic rather than war. The recovery of the civilization had just started when the depredations of the slave trade was visited on the people and with it the colonial interregnum. History teaches that unlike the situation in other parts of Nigeria and West African, the occupation of Igboland was a protracted and piece-meal affair, which was achieved literally village by village as a result of the decentralised political organisation of the people.

While this must account for the republican temper of the people, it has also bred a short-term perspective in the people’s appreciation of their history which can often be mistaken for a lack of the sense of history. What is more, it does explain to some extent, the misunderstanding and underrating of the achievements of the culture by the colonial authorities. The important point to note is that the history, politics and culture of the Igbos bear the imprint of their ancient origin, of their adaptation over the centuries to their environment and of their salient difference from their latter day compatriots, the Yorubas and the Hausas. When the Igbo man attempts, often unsuccessfully, to imitate the political and cultural usages of these latter day compatriots, he does a grave injustice to himself and to his roots.

The justly recognized, feared even if resented industry, drive and intelligence of the Igbos are the consequences of their successful adaptation and acculturation to their forest environment. “Man know thyself” is an advice that the Igbo can use with great benefit and which should breed in them a degree of circumspection, caution and discretion in the adoption of foreign modes and usages rather than the loud and often ostentation mien that we present to the outsider. It should breed in us a resilience of spirit and an inward looking and proud affirmation of who we are rather than the self-deprecating and whining disposition that seems to have overtaken us and particularly the younger generation. For it must be stated with some pride that the zest and zeal with which our people embraced western education and which enabled them in thirty short years (1934 1964) to overtake and some may say to “dominate” the social, political and economic landscape of modern Nigeria was unprecedented. Indeed, the exploits of the scientists and professionals in the Biafran war and after were in itself a worthy testament of the genius and resilient spirit of our people. No other African group in modern times have shown as much pluck and serendipity. There is, therefore, a lot to be proud of.

The contemporary state of the Igbo nation Most unfortunately, the current reality and portents extant in the Igbo heartland are different and often discouraging. On the social front, we project a picture of a society, which is not only fraying at the edges but one whose centre seems unable to hold together. From one homestead to another, from one community to the next and indeed throughout the five states of the Igbo homeland, there is disaffection and a general lack of the sense of solidarity and social harmony; chieftaincy disputes, violent crimes, youth restiveness, lack of trust in one another is shown in various ways. It is often as if no one in particular is in charge. There is a general lack of respect for the elders and for the leaders.

On the political front, it is as if there are no more rules. It is no longer the politics of service and decorum as we say in the days of Zik and Okpara but rather a cash and carry political system in which the highest bidder is the victor no matter how unsavoury his/her political past may have been. The leaders of the political system at the local, state and national level are often men of questionable credentials and past. It is as if a sense of responsibility and integrity have become hindrances rather aid to the emergence and sustenance of a leadership elite that cares and serves the people.

The result is the abandonment of the politics of principles and ideas for the rule of the mob-thugs and toughies are often the ones that dictate political outcomes. The result has been a general repudiation and lack of interest in the affairs of the community and the state by members of the professional and leadership elite. The debacle in Anambra State over the last six years is merely the inescapable demonstration of the general lack of leadership and the requisite sense of propriety and responsible social values in the wider community. Known 419ners and others of known disrepute have often metamorphosed into our “leader” while men of quality, of reason and decorum appear helpless and listless. The invasion of the traditional institutions by these flight-by-night “leaders” is the most vivid illustration of the social dysfunction that has become the measure of the state of depravity and dissonance in our body politic.

The harvest has been the collapse of our economic centres of Aba and Onitsha. Yes, what passes for business still goes on there but the army of unemployed and the declining numbers in the schools remain a testimony and a reminder that governance has taken leave of the pursuit of the welfare of the people and the maximization of the common good. On the farms and in the markets, the daily grind to make a living takes its toll on the health and the well being of our citizens with the unkempt and unsanitary conditions of daily existence in our towns. While erosion ravages the land, the flight of the young and able-bodied men and women from Igboland to the slums of Lagos, Abuja and even Port Harcourt is a constant reminder of the failure of our collective leadership in Igboland. As the able bodied and gifted youth pour out of the Igbo heart land, the rhetoric of our “leaders” rise in its strident proclamation of the good they have done and against all the evidence of decay and decline. What can be done? How did we get to this pass?

Nigeria’s Igbo problem and the Igbo dilemma in Nigeria There is inherent paradox and contradiction in the Igboman’s place in Nigeria. On the one hand given his industry, his intelligence and his enterprise, the Igboman is a desirable gift to Nigeria and the stuff of which great nations and great civilizations can be built. On the other hand, given his presumptive confidence in his abilities and his unabashed hunger to succeed at whatever cost, he engenders fear and unwelcome visibility amongst his compatriots. His lack of subtlety, his drive to overcome and his insatiable “greed” for material progress engenders resentment often inexplicable, and perhaps, undeserved hostility in the host communities. His “loud” style of life and the facility with which he can adapt to and adopt new ways can also be unsettling to foreign cultural formations that have come in contact with the Igbos including the colonial masters. There is thus an underlying sense of conflict in the Igbo presence in Nigeria.

As had been noted, Igbo society developed in the tropical forests of South Eastern Nigeria. While this honed the individualism and independent spirit of daring, it also engendered an isolationist tendency within which the population increased and prospered in its simplicity and self-satisfied balance in its environment. Colonial interregnum enabled the Igbo to pour out of the South Eastern parts to the rest of Nigeria and beyond. The simple ways of life belied the sophistication and ancient origin of the culture. This bred an attitude in those who came into contact with the Igbo that often under-rated and even misread or misunderstood the dynamism and effervescence of the Igbo spirit and character. The prejudices and hostility that has bedevilled the relationship of the Igbos with their other Nigerian compatriots has its roots in this misunderstanding: it can be unsettling to the human psyche to be worsted by those you had under-rated and would have preferred to use for your benefit or even ignore. The love-hate basis of such a relationship can create instability unless skilfully managed with wisdom, tolerance and patience. This is Nigeria’s Igbo problem. What is more: patience is at a discount in the Igbo scale of values. Thus, other nationalities in Nigeria despite mutual antagonism are often united by their common hostility and fear of the “upstart”. The challenge that confronts the Igboman is how to reconcile his drive for that which is good with discretion and a patient tolerance and understanding of other ways. Alas, for the Igbo, there are no half-measures, he will adopt foreign ways, hook line and sinker or he would impatiently display his intolerance of foreign ways. Nigeria and Nigerians would want to use the genius of the Igbos without paying for it. But Nigeria needs the Igbo as the Igbos need Nigeria. What then is the point resolution, the center of balance?

The place of the Igbo in Nigerian politics and the economy Neither the history of politics nor the economy in Nigeria would be complete without mention of the dominant place of the Igbos in the pre-Biafran war in Nigeria. As I have had cause to observe elsewhere, the period between 1934 and 1964 in Nigerian history, politics and economy development can justly be called the Igbo epoch. From 1934 which marked the graduation of the first generation of western educated Igbo leaders such as Azikiwe and Mbanefo to 1964, the onset of the Nigerian crisis which was to lead eventually to war, the frenzied pursuit of education was an Igbo rally cry and preoccupation. Many Igbo communities were activated and mobilized to sponsor gifted and brilliant youngsters, without consideration of kinship ties, to overseas universities and later to the only Nigerian institution of university standing then in existence, the University College, Ibadan for further studies.

The result was an avalanche of youthful and well-educated leaders in politics, the economy, in the professions and the army that Igboland provided to Nigeria. Such men as Mbonu Ojike, Nwapa Emole, Kenneth Dike, Osadebe, Odumegwu Ojukwu, Imoke, Ugochukwu and a host of other worthy Igbos were products of the frenetic onslaught of the Igbos on western education and the western style of economy. The pay off was that in civil service, the universities, the professions and the army, the Igbos were certainly visible, if not dominant despite the head start of two generations that their Yoruba compatriots had on them. Even in the fight for Nigeria independence, the venerable Obafemi Awolowo was a late-comer when compared with the time of entry and impact of Azikiwe, Mbonu Ojike, Alvan Ikoku, etc. All that headroom was lost with the war.

RETURN

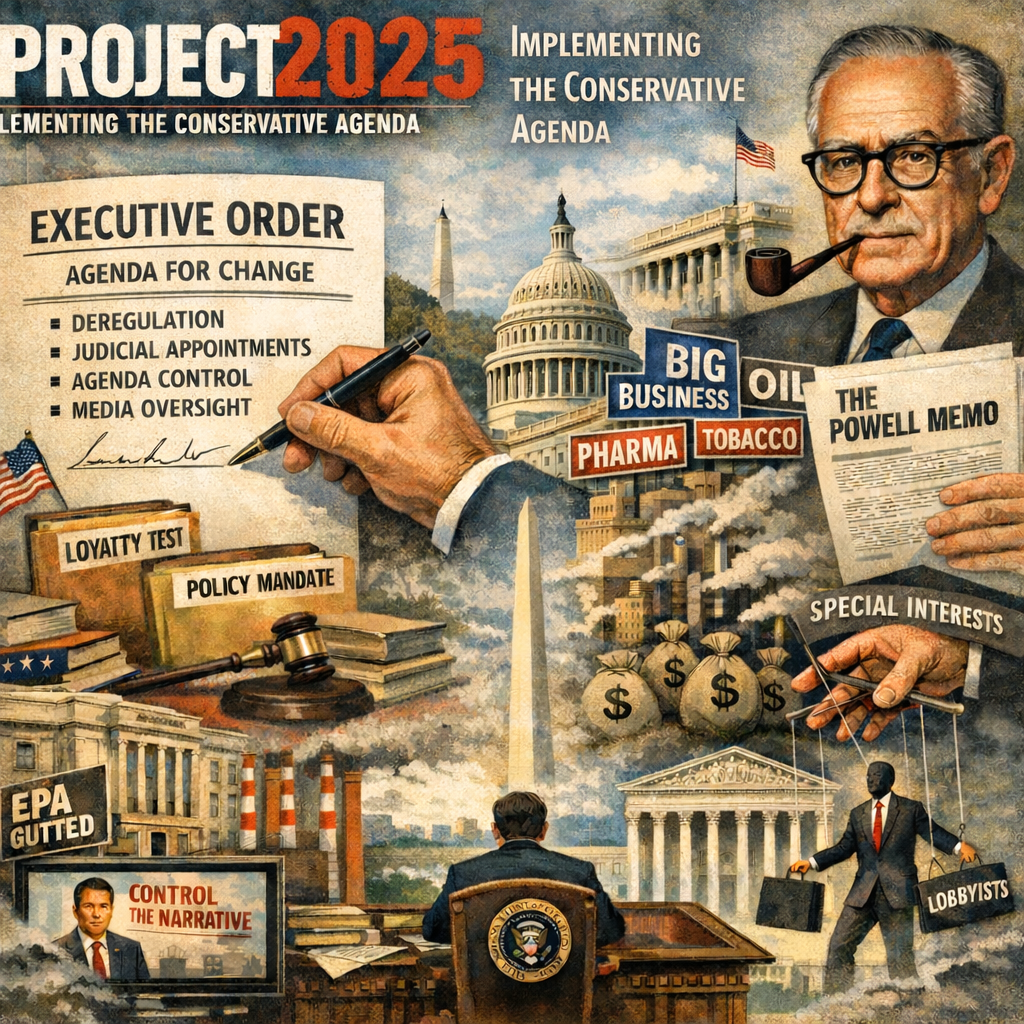

From the Powell Memo to Project 2025: How a 1971 Corporate Strategy Became a Global Template for Power In August 1971, a corporate lawyer named L...

The Market’s Mood Ring: How Volatility Across Assets Traces a Hidden Geometry of SentimentIf you want a fast, honest way to describe modern markets,...

Nigeria’s grid collapses are not ‘bad luck’ – They are a design failure, and we know how to fix themFirst published in VANGUARD on February 3,...

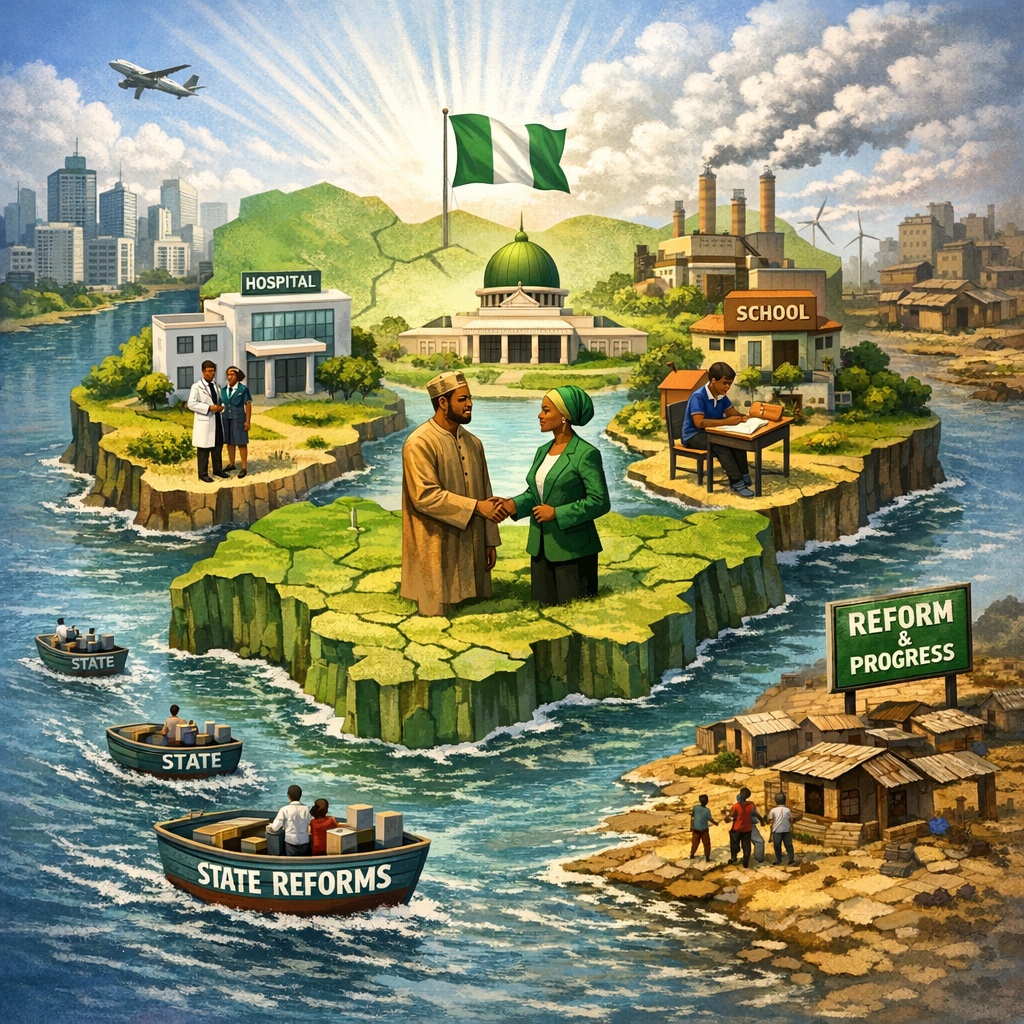

Islands of Credibility: Nigeria’s Best Reform Strategy Starts in the StatesFirst published in VANGUARD on January 31, 2026 https://www.vanguard...

Project 2025 Agenda and Healthcare in NigeriaThe US and Nigeria signed a five-year $5.1B Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on December 19, 2025, to bo...