culled from GUARDIAN, July 20, 2005

"On account of its gross mismanagement of the economy, involving wasteful squandering of oil money on frivolous festivals, Trade Fairs (in which Nigeria had nothing to sell but everything to buy), inflated construction contracts and the like, Obasanjo's regime drove Nigeria into financial bankruptcy by 1977. Nigeria, in spite of her oil wealth, was forced into the imperialist "debt trap" again." * Professor Bade Onimode, Imperialism and Underdevelopment in Nigeria, Macmillan, 1983, p. 206.

It is so tragic that as a nation we have such a short historic memory. We tend most times to react reflexively to events as they occur without allowing the lessons of yesterday to inform the present for the benefit of the future. This flaw in our national character was very much evident in most reactions to the recent debt relief granted Nigeria by the Paris Club of Creditors. There was first of all the euphoric, self congratulatory national broadcast by President Olusegun Obasanjo whose government, in his first outing as military Head of State, set Nigeria on the path of humiliating debt peonage in the first place.

The President naturally feels that the substantial debt relief secured for Nigeria vindicates his endless trips across the globe over the last six years and many commentators appear to agree with him. Well, I am yet to come across any thorough content analysis of Mr. President's trips to enable us know how many were actually in pursuit of debt relief. Moreover, it will be interesting to find out if the leaders of other countries also granted debt relief had to expend so much money on so many trips to achieve the objective. Afterall is this not an age when the communications revolution has made it possible to transact the most complex businesses across vast distances without the inconvenience of physical dislocation?

Following the President's broadcast, I have read newspaper columnist after columnist heaping encomiums on him and describing the debt relief as a democracy dividend. No wonder that when he appeared on his last monthly media chat alongside the Finance Minister, Dr Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala and the Speaker of the House of Representatives, Alhaji Bello Masari, the mood was a celebratory one. Mr. President glowed with pride. Dr Okonjo-Iweala beamed with joy. Mr. Speaker's face, however, was rather inscrutable. Virtually all the callers were falling over each other to congratulate the President, our new redeemer from the mortal sin of indebtedness.

What really was all the celebration and back biting about I wondered? Had we launched a Satellite into space, discovered the cure for an incurable disease, maintained even one year of uninterrupted electricity or produced another Nobel laureate after our own WS, I would understand the self-indulgent backslapping. But a richly endowed country like ours, blessed with diverse mineral and natural resources, harbouring some of the most gifted, resourceful and resilient people on the face of the earth simply has no business celebrating the partial forgiveness of a debt that was recklessly, needlessly and shamelessly accumulated in the first place. Honestly, we deserve to be collectively spanked like spoilt, prodigal children.

On a purely theoretical plane, I find it intriguing that economists of the IMF/World Bank orthodox school, which was largely responsible for the policies that led to the protracted economic crisis of the last three decades including our indebtedness, are today once again at the helm of our economic affairs. These were the champions of the Import-Substitution model of Industrialisation, which was heavily dependent on foreign exchange especially for the importation of spare parts and machinery. The sharp drop in oil revenues in 1977 exposed the limitations of this industrialisation strategy and the resultant foreign exchange crisis forced the Obasanjo military regime to take the first Jumbo Euro-Dollar loan of N1 billion. With the acquisition of this loan, Nigeria's indebtedness, which stood at N82.4 million in 1960 and had risen to N496.9 million in 1977, jumped astronomically to over N1.5 billion in 1978.

It is indeed amazing, as Professor Adebayo Olukoshi notes that "Although specific projects were listed for execution under the loan application, the actual disbursement of the Euro - dollar loan and the plan for its repayment, which was to be done in four installments, were unrelated to the profitability or even viability of the projects". The country plunged deeper into the debt morass when the military regime negotiated another Euro-market loan of $1.145 billion "on terms similar to the first loan and for basically similar projects". Yet today economists of this persuasion are in charge of our reforms and advising us to make sacrifice after sacrifice while waiting endlessly for the promised El Dorado.

I again find it strange that we all seem to believe that Nigeria is solely responsible for the debt crisis and therefore owe our creditors a world of gratitude for benevolently granting us debt relief. Nothing could be further from the truth. In reality, given the negative impact of soaring energy costs on western economies following the OPEC - induced sharp increase in Oil prices in 1973, the creditors needed to lend money to developing countries as desperately as the latter needed to borrow. Professor Claude Ake illuminates this point with characteristic simplicity thus: "The debt of developing countries was partly a product of the decade 1974 - 84, when the effective cartel strategy of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) produced the great oil boom. Some of the surplus earned by OPEC members found its way to the industrialized market economies, whose banks began to have excess liquidity. Since the economic slack resulting from high-energy costs had dampened the demand for capital, those economies began to encourage developing countries to borrow money to mop up the excess liquidity. In some cases, such as Nigeria, which was seen as having good prospects, credit was liberally extended".

The creditors are as culpable as the debtors for the confounding debt crisis. While the debtors are to blame for not investing the credit obtained wisely, the creditors too recklessly loaned out money to largely unviable projects without thorough risk assessment or even a cursory understanding of the economies of borrowing countries. In her explosive book, A Fate worse Than Debt, Susan George gives a graphic description of how desperate 'loan hunters' from western banks flooded Africa offering loans to governments on juicy, irresistible terms.

A progressive Nigerian government, therefore, ought to utilise our immense clout to mobilize Africa for a collective position on resolving the debt impasse with both creditors and debtors bearing a joint responsibility for their mutual errors. Furthermore, there is absolutely no reason why we should not have adopted and intensified the reparations campaign of the late MKO Abiola thus balancing the debt claims of the creditors with the even more devastating impact of the slave trade and colonialism on the psyche as well as social, political and economic systems of Africa.

Is there any objective basis for the optimism in some quarters that the debt relief will promote the cause of development in Nigeria through new opportunities for investment in health, education and public infrastructure? I sincerely don't see any. The problem with the development process in Nigeria is not necessarily the paucity of funds but the very structure of the state and the character of its operatives. Sadly, the Nigerian State, despite all the antic - corruption rhetoric, remains a means of primitive accumulation for the private enrichment of a rapacious, parasitic elite who control its levers. Matters are not helped by the excessive centralization of its functions, inequitable federally skewed allocation of revenue and the immense powers of an imperial presidency that operates with scant regard for the Rule of Law. All of these combine to reinforce corruption, promote inefficiency and undermine development. If the structural roots of Nigeria's socio - political and economic crises are not decisively addressed, not even the cancellation of all our debts will resolve the dilemma of underdevelopment.

As we await the Policy Support Instrument (PSI), which we are to negotiate with the IMF as a condition for debt relief, I foresee this deal ushering in a new era of recolonisation of Nigeria. Of course we will continue to exhibit all the outward trappings of sovereign autonomy - a flag, a national anthem, security forces to contain a captured citizenry etc. And there will be no white colonial faces running our governments and other institutions. But our economic policy and destiny, the critical sub-structure on which rests the political, legal and social super - structure, will be firmly controlled by those without whose aid and 'debt relief' we apparently cannot survive. How sad a fate it is for us. But then a people who cannot responsibly manage their affairs deserve to be managed by others.

* Ayobolu is a Special Adviser on Information with the Lagos State Government

RETURN

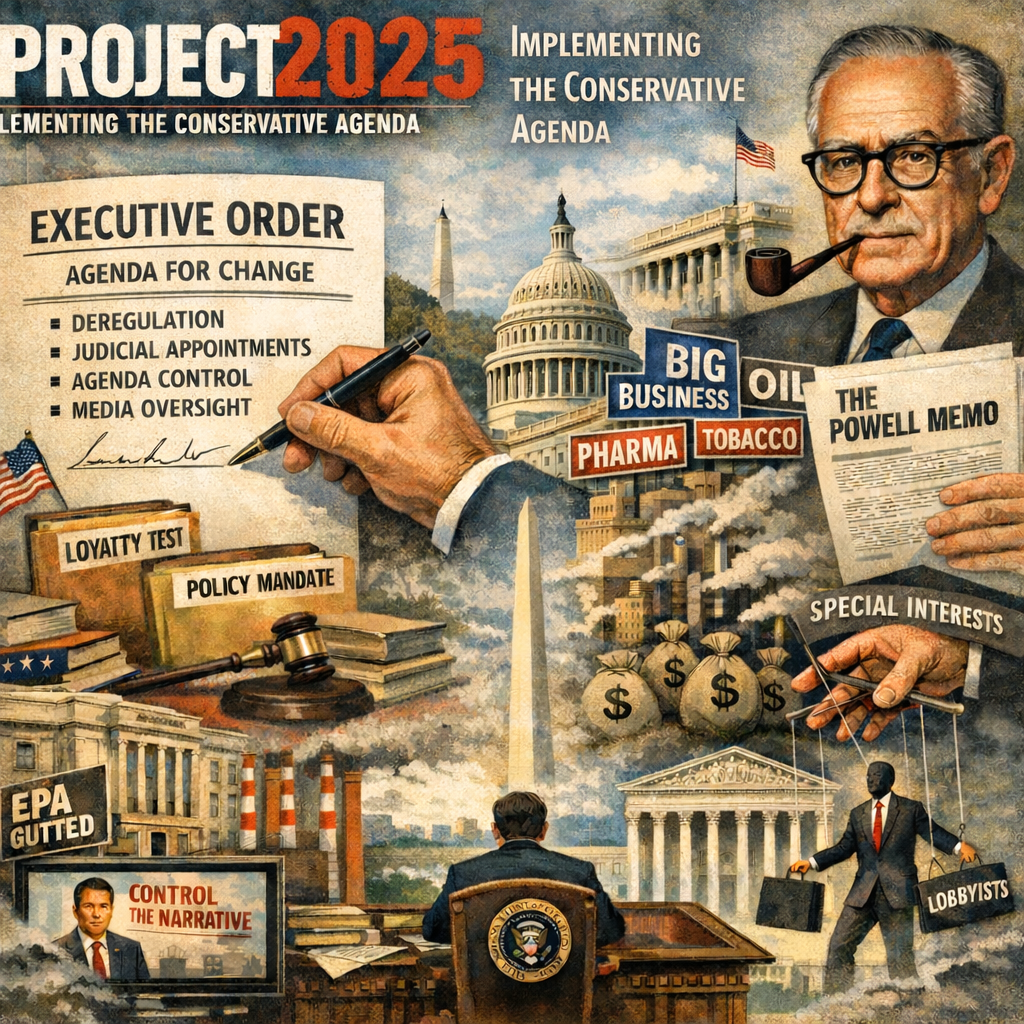

From the Powell Memo to Project 2025: How a 1971 Corporate Strategy Became a Global Template for Power In August 1971, a corporate lawyer named L...

The Market’s Mood Ring: How Volatility Across Assets Traces a Hidden Geometry of SentimentIf you want a fast, honest way to describe modern markets,...

Nigeria’s grid collapses are not ‘bad luck’ – They are a design failure, and we know how to fix themFirst published in VANGUARD on February 3,...

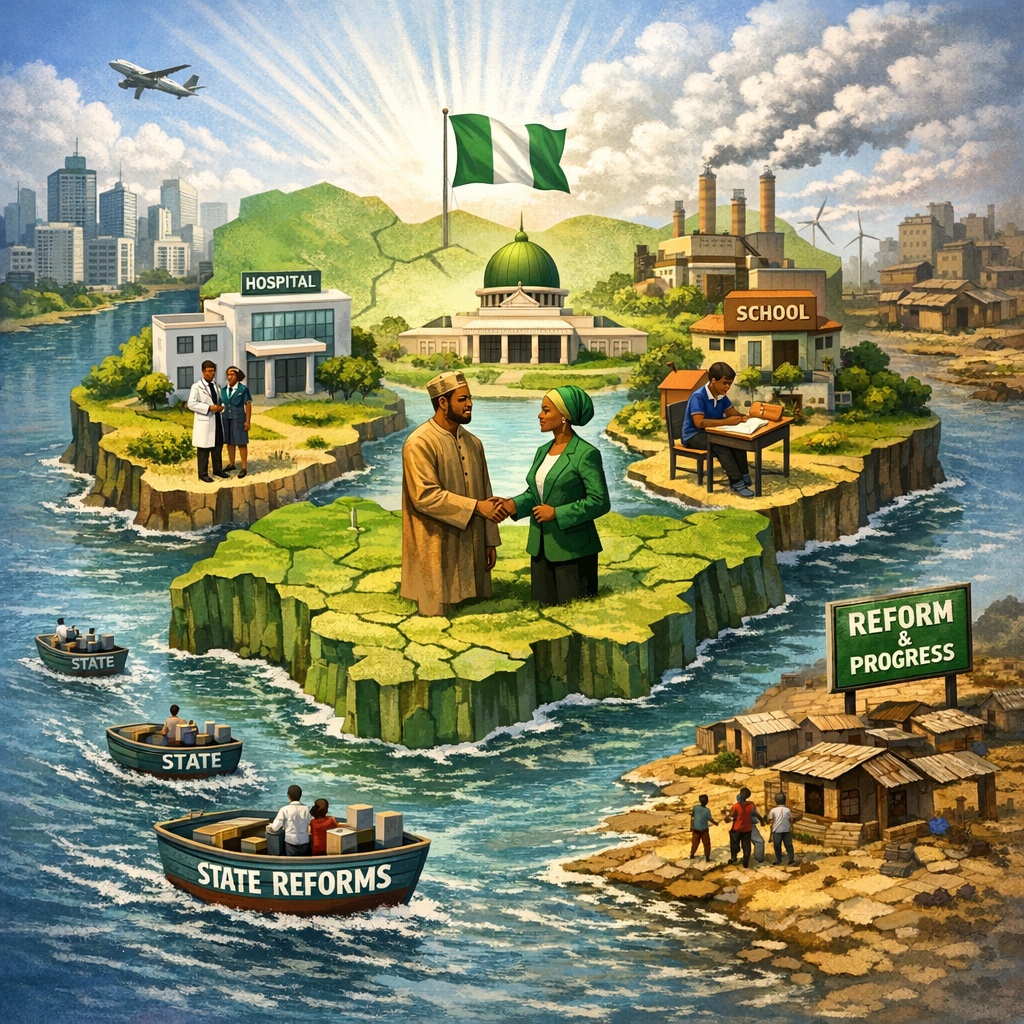

Islands of Credibility: Nigeria’s Best Reform Strategy Starts in the StatesFirst published in VANGUARD on January 31, 2026 https://www.vanguard...

Project 2025 Agenda and Healthcare in NigeriaThe US and Nigeria signed a five-year $5.1B Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on December 19, 2025, to bo...