A Prescription for Marxism

By Kenneth Rogoff

Foreign Policy/Jan-Feb 2005

The next great battle between socialism and capitalism will be waged over human

health.

Karl Marx may have suffered a second death at the end of the last century, but

look for a spirited comeback in this one. The next great battle between

socialism and capitalism will be waged over human health and life expectancy. As

rich countries grow richer, and as healthcare technology continues to improve,

people will spend ever-growing shares of their income on living longer and

healthier lives. U.S. healthcare costs have already reached 15 percent of annual

national income and could exceed 30 percent by the middle of this century?and

other industrialized nations are not far behind. Certainly, an aging population

is part of the story. But if economic productivity keeps growing at its current

extraordinary pace, Europeans, Japanese, and Americans could triple their

current income per person by 2050. Inevitably, we will spend a lot of that

income on improving and maintaining our health.

This brings us to Marx. When the price of medical care takes up just a small

percentage of national income, it is hard to argue with the notion that everyone

should enjoy similar medical treatment. Sure, critics may gripe that the higher

taxes needed to pay for universal health coverage may cut into economic growth a

bit, but so what? A little redistribution won't suddenly transform the United

States into a failed, Soviet-style "workers' paradise." But as health costs

creep up to, say, 25 percent of national income, things get more complicated.

Americans would see their tax bills more than double, while total taxes could

reach 75 percent of many Europeans' income. With oppressive tax burdens and

heavy state intervention in health already the largest sector of the economy,

socialism would have crept in through the back door.

Of course, smug Europeans, Canadians, or Japanese may think that exploding

healthcare costs are a purely U.S. problem. Certainly, the British and Canadian

governments successfully wield their monopolies over healthcare to hold down

both doctors' incomes and prescription drug prices. And part of the rise in U.S.

healthcare costs stems from the breakdown of the checks and balances that more

centralized systems provide. (For example, Americans are several times more

likely to receive heart bypass surgery than Canadians, where the procedure is

reserved for extreme cases. Yet several studies suggest that patients are no

worse off in Canada than in the United States.) And even the most fanatical free

marketers recognize that healthcare is different from other markets, and that

the standard supply-and-demand principles don't necessarily apply. Consumers

have poor information, and there is an obvious case for greater government

involvement than in other markets.

But if all countries squeezed profits in the health sector the way Europe and

Canada do, there would be much less global innovation in medical technology.

Today, the whole world benefits freely from advances in health technology that

are driven largely by the allure of the profitable U.S. market. If the United

States joins other nations in having more socialized medicine, the current pace

of technology improvements might well grind to a halt. Even as the status quo

persists, I wonder how content Europeans and Canadians will remain as their

healthcare needs become more expensive and diverse. There are already signs of

growing dissatisfaction with the quality of all but the most basic services. In

Canada, the horrific delays for elective surgery remind one of waiting for a car

in the old Soviet bloc. And despite British Chancellor Gordon Brown's determined

efforts to rebuild the country's scandalously dilapidated public hospital

system, anyone who can afford to go elsewhere usually does. With public

healthcare systems fraying at the edges, many countries outside the United

States increasingly face the need to allow a greater play of market forces.

During the next few decades, modern societies will wrestle with very tough

questions and tradeoffs: What, exactly, are people's basic health needs in an

era where medical technology relentlessly advances the frontiers of the

possible? How do we help people while still giving them the incentive to

economize on their use of scarce healthcare resources? And who plays God?the

bureaucrats, the doctors, or the forces of the market? Ultimately, the case for

some government intervention and regulation in health care is compelling on the

grounds of efficiency (because costs are out of control) and moral justice

(because our societies rightly take a more egalitarian view of health than of

material possessions). The issue is precisely how much redistribution of income

and government intervention is warranted. With the health sector on track to

make up almost a third of economic activity later this century, the next great

battle between capitalism and socialism is already underway.

Copyright Carnegie Endowment for International Peace Jan/Feb 2005 | Kenneth

Rogoff, FOREIGN POLICY'S economics columnist, is professor of economics and

Thomas D. Cabot professor of public policy at Harvard University.

RETURN

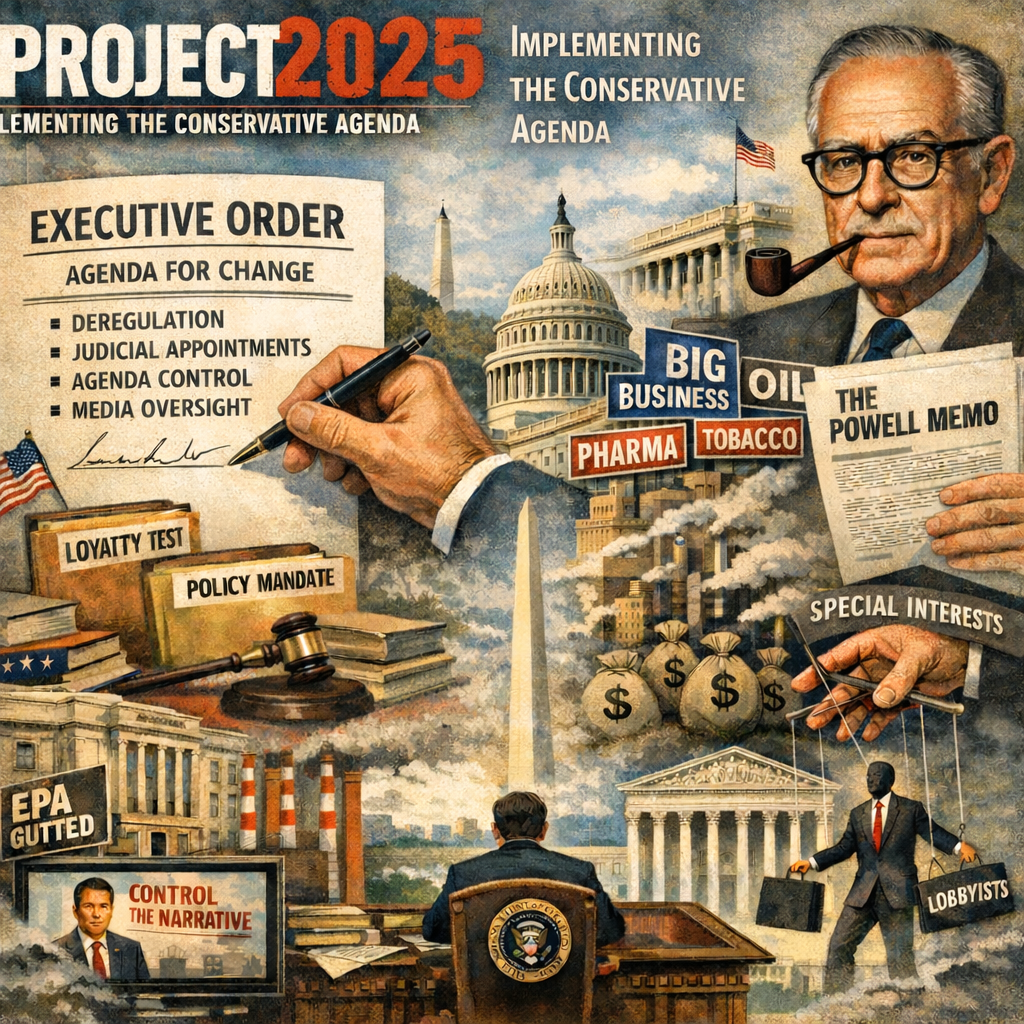

From the Powell Memo to Project 2025: How a 1971 Corporate Strategy Became a Global Template for Power In August 1971, a corporate lawyer named L...

The Market’s Mood Ring: How Volatility Across Assets Traces a Hidden Geometry of SentimentIf you want a fast, honest way to describe modern markets,...

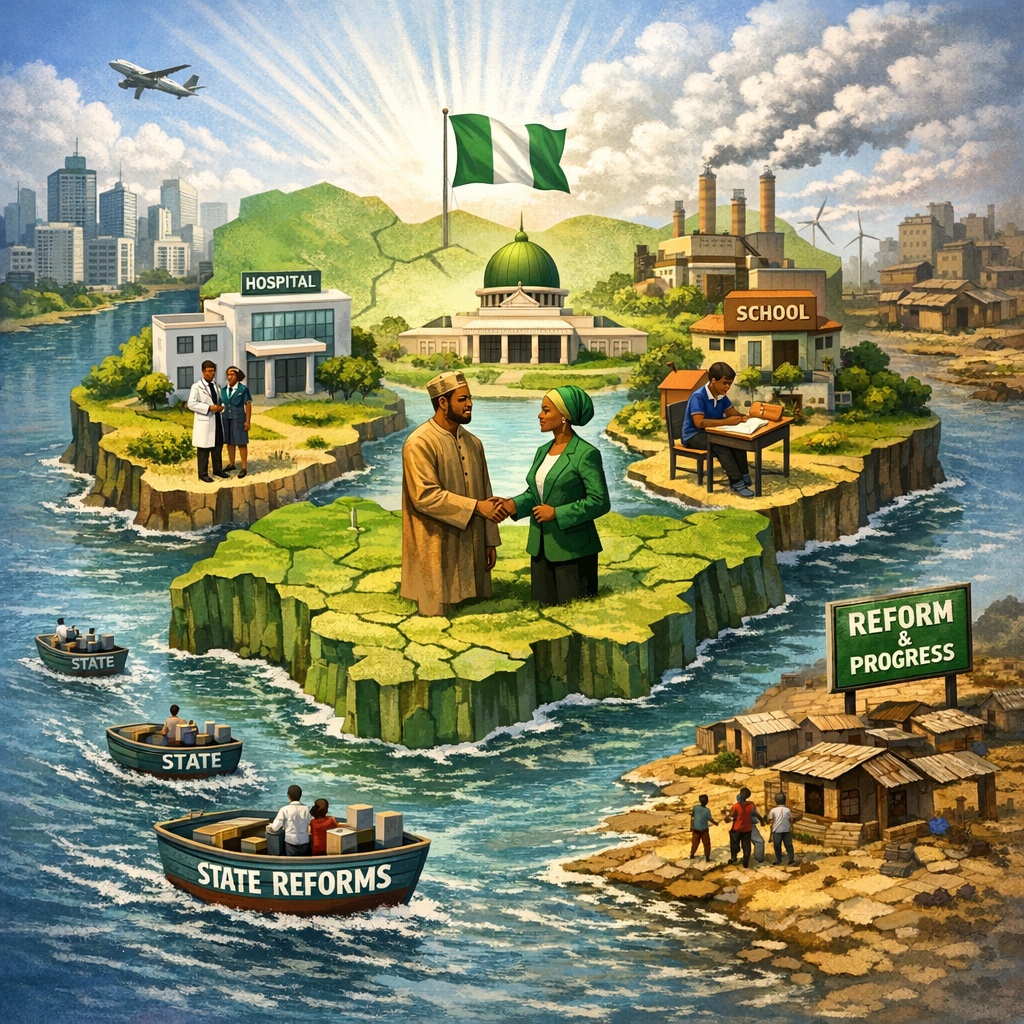

Nigeria’s grid collapses are not ‘bad luck’ – They are a design failure, and we know how to fix themFirst published in VANGUARD on February 3,...

Islands of Credibility: Nigeria’s Best Reform Strategy Starts in the StatesFirst published in VANGUARD on January 31, 2026 https://www.vanguard...

Project 2025 Agenda and Healthcare in NigeriaThe US and Nigeria signed a five-year $5.1B Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on December 19, 2025, to bo...