continued from http://www.dawodu.com/omoigui25.htm

By

Nowa Omoigui

OWERRI, 1969 - PART 3

Carl von Clausewitz once wrote that

"Tactics is the art of using troops in battle; strategy is the art of using

battles to win the war."

Indeed, over the centuries, military

theorists and practitioners have sought to develop and implement principles of

war, as well as the tactical and strategic maneuvers essential to victory. It

is not uncommon to hear military theorists describe the bedrock of warfare as

consisting of (a) the identification of an objective, (b) taking the offensive,

(c) retaining the element of surprise, including stealth and deception, (d)

maintaining operational security and force protection, (e) ensuring unity of

command, (f) efficient and economical use of force, (g) concentration of

superior force(s) at the decisive point(s), also known as the principle of mass,

and last but not the least, (h) the deployment of forces through maneuver,

to ensure retaining all the hitherto mentioned advantages of offense, surprise,

security (protection), unity of command, economy of force, and mass. To these

core principles others have suggested subsidiary but no less important

principles, like administration. And to the long list of “principles”

must be factored such imponderables like luck, style of command, quality

of intelligence, and timeliness of response to good intelligence.

Nevertheless, it seems apparent that the

mechanics of offensive maneuver are essential to eventual attainment of military

objectives, no matter the era of warfare. Such maneuvers include (a) Frontal

assault by penetration of the center (i.e. “Head-on collision”) or breaking

through gaps between enemy units, (b) single envelopment, (c) double

envelopment, (d) defensive-offensive feints, (e) turning movements, (f) hot

pursuit, (g) Razzia /Hornet's Tactic, etc.

Enveloping

maneuvers seek to surround (envelope) the enemy using ground troops, airborne or

amphibious forces. In single envelopment, the maneuver, using ground

troops, is directed against one enemy flank or around one enemy flank to attack

the rear. In double envelopment, two attacking groups of ground troops

swing around the flanks of the enemy position either to attack the flanks

directly or destroy targets in the rear primarily to disrupt communications or

retreat, while a secondary or diversionary group attacks the enemy from the

front. In vertical envelopment, airborne troops are dropped behind

enemy lines to seize important targets, disrupt coordination and communications,

and/or prevent retreat. In amphibious envelopment, the same objectives

are attained using amphibious (sea or river borne) forces.

One way to

illustrate the concept of single envelopment is to think of one's hands. If,

standing in front of a hypothetical enemy, one were to swing an outstretched

upper arm, forearm and hand (left or right) to grab him (or her) from behind and

pull him (or her) in closer for the coup de Grace, one would have single

enveloped the enemy. If both upper limbs are used to swing around and bring him

(or her) into a bear hug, one would have double enveloped the enemy. Double

envelopment is also called "pincer movement" because of the shape of a pincer.

Single envelopment was used by Alexander

the Great during the battle of Arbela in 331 BC. US Confederate Generals

Robert Lee and “Stonewall” Jackson also employed it successfully at the battle

of Chancellorsville in 1863. In his quest to evict the British Eight Army from

Libya and capture the strategic port of Tobruk, German General Erwin Rommel

swung the powerful 15th Panzer Division, supported by Italian

infantry around Bir el Harmat on June 12th, 1942, attacking the

British from the side and rear, causing considerable chaos and eventual defeat.

To this short but by no means exclusive list of fascinating historical examples

one should add the first Persian Gulf War of 1991, during which American General

Norman Schwarzkopf used the

principle of single envelopment to outflank Iraqi forces in Kuwait.

On the other hand, the

first recorded use in military history of the principle of "double envelopment"

was at the Battle of Cannae, on August 2nd, 216 BC, between Carthaginian troops

under Hannibal and Roman troops under Consul Terentius Varro. The superior

Roman Army of 79,000 men was routed and destroyed by 50,000 men under Hannibal

whose backs were against the sea. A similar principle was used in 1781 at

Cowpens during the American Revolutionary War against Britain. During the

Second World War, the 7th German Army was double enveloped in August 1944 at the

Argentan-Falaise Gap by the US Fifth Armored Division, supported by

Canadian, British and Polish forces.

The failure to completely close the Argentan-Falaise gap

has been ascribed to a controversial decision made by Lt. Gen. Omar

Bradley, then commanding the 12th U.S. Army Group. He stopped the link-up of

the XV Corps of Lt. Gen. George S. Patton's Third Army with Lt. Gen. Henry D. G.

Crerar's First Canadian Army moving south from Caen toward Falaise for fear of

accidental friendly fire, among other reasons. Through the gap thus created,

many beleaguered German units escaped.

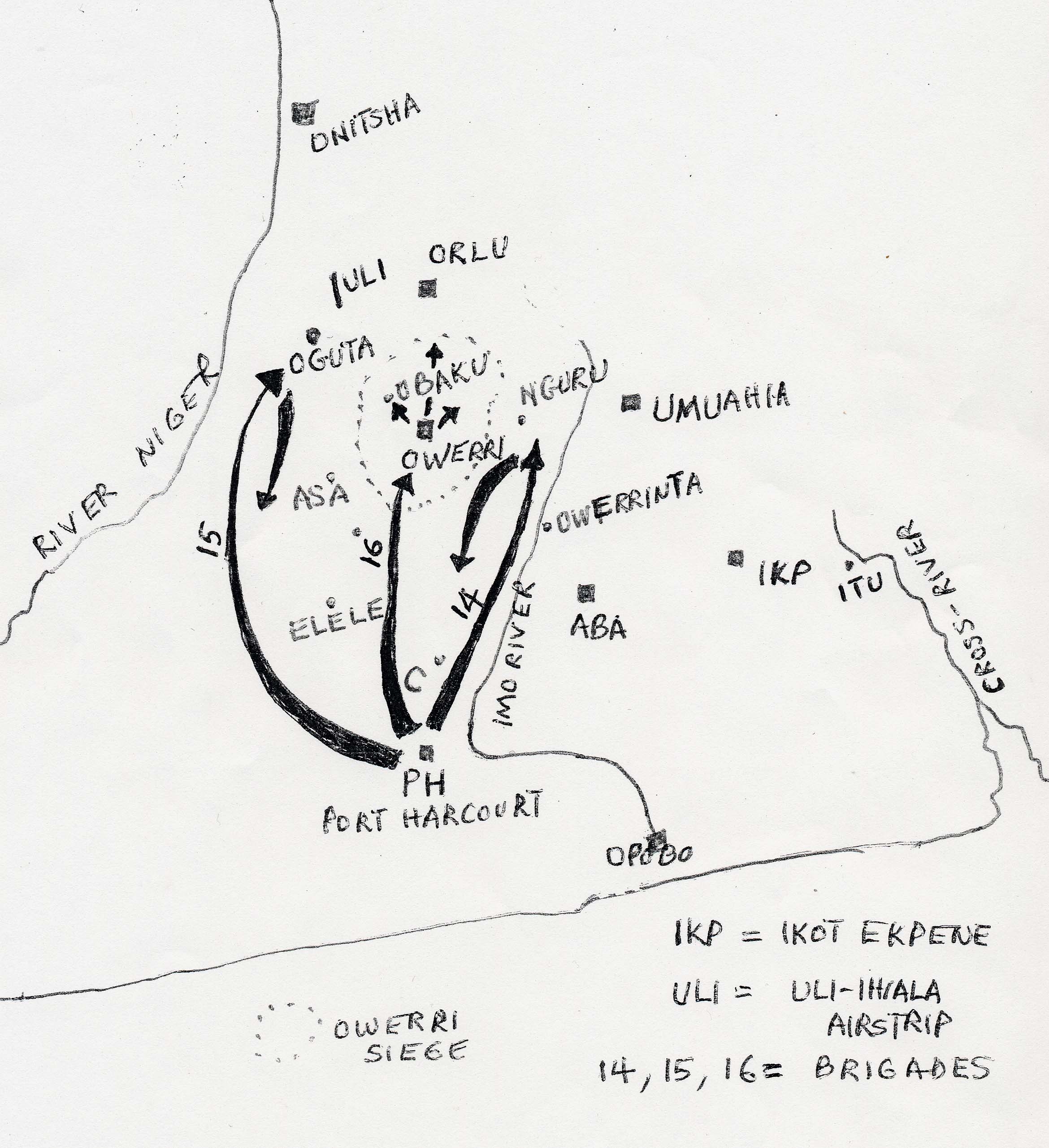

The initial assault and capture of the strategic

town of Owerri – which was then in part the capital of Biafra - was

conceptualized in 1968 by Colonel Benjamin Adekunle (aka “Black Scorpion”) along

three axes assigned to the 14th, 15th and 16th

Brigades of the 3MCDO, under Majors George Innih, Yemi Alabi (later Makanjuola)

and E.A. Etuk, respectively. Etuk had previously been the successful Commanding

Officer of the 8th Battalion along the Calabar-Itu-Ikot Ekpene axis

before being redeployed to his new Brigade command for the push into Port

Harcourt and dash to Owerri.

|

|

Supported by mortars and artillery, Captain

Isemede’s 12 Bde was to protect the left flank of Major Shande’s 17 Bde as he

crossed the Imo River, ultimately taking the market town of Aba on September 4th.

Meanwhile, Etuk’s 16 Bde was to charge head on from Port-Harcourt in a

‘penetration of the center’ toward Owerri. Innih’s 14th Bde was to

protect Etuk’s right flank by advancing on to Owerrinta (between Etuk and

Isemede) while Makanjuola’s 15th Bde was to swing left of Owerri,

bypassing Ohoba in an ambitious river-borne assault on Oguta. From here they

hoped to simultaneously threaten Biafra’s connection to the outside world at

Uli-Ihiala airstrip six miles away, cut off Biafra’s source of fuel at the

Egbema oil field, and prevent Biafran reinforcements from reaching Owerri.

Innih and Isemede would then swing north and left and later link up with

Makanjuola, north of Owerri, securing the position of Etuk inside Owerri,

effectively ending the war. Unfortunately, as is so often the case in war, the

plan did not survive contact with opposing Biafran forces.

Led by its 33rd Battalion, supported by

armoured vehicles, mortars and artillery, the 16th Bde pushed into

Owerri on September 16, a day after Makanjuola had to abandon his position at

Oguta with heavy losses in the face of fierce Biafran counter-attacks led by

Colonel Nwajei, Captain Anuku and Colonel Joe Achuzia. Major Asoya subsequently

dislodged Federal units of the 15th Bde from the Egbema oil field. Etuk,

meanwhile, had advanced furiously against units of the Biafran 14th

Division (then under Colonel Nwajei) from Port-Harcourt, through Elele, Awarra,

Asa, Ohoba, Avu, Obinze, and finally to Owerri itself. Although unintended,

what Colonel Nwajei achieved by default in failing to stop Etuk’s advance

(allegedly due to lack of ammunition) was to “retreat his base”, thus setting

Etuk up for the kill as the Biafran flanks on either side of Owerri moved

forward against Innih and Makanjuola. Nevertheless, Biafran leader Ojukwu

replaced Nwajei, now suspected of “sabotage”, as commander of the 14th

Division. Colonel Ogbugo Kalu, a one time Commandant of the Nigerian Military

Training College, who had earlier been branded a “saboteur” after the fall of

Port Harcourt, took Nwajei’s place.

On Etuk’s right flank, Innih’s push against the

Biafran 63 Bde to Inyiogugu, along the Owerri-Umuahia road, north of Owerrinta,

was bogged down one mile to Inyiogugu. Counter-attacks by Biafran commandos

against Innih’s units were led initially by the mercenary, Colonel Steiner

(until he fell out with his hosts), and later the reinvigorated 63 Bde under

Major Lambert Ihenacho along with a battalion from the new “S” division led by

Colonel Onwuategwu. (The “S” Division had been created after the fall of Aba).

During the battle for Inyiogugu, Biafran home made “Ogbunigwe” mines were used

with devastating effect and French weapons began to arrive in increasing

quantity. The 14th Bde fell back southwards in disarray all the way

to Elelem and Amala.

For a full twenty-one (21) days, the 16th

Bde, now dug in inside Owerri, could not make any contact with nor get

information about the 14th and 15th Bdes on either side of

it. As noted above, the two sister brigades were supposed to protect its

flanks and prevent Biafran counter-attacks. Instead they were concerned with

their own very survival at that point, retreating in chaos, thus exposing the 16th

to an uncertain fate inside the Owerri salient in the absence of an outright

order to evacuate. Nevertheless, Etuk tried to relieve pressure on his sister

brigades by attempting to use his momentum

to puncture the outstretched Biafran base and create an opening to attack

Biafran forces on his left and right from the rear. He did this by

1. Pushing

along the Owerri-Okigwe road toward Mbieri and Orodo aiming at Orlu and Nkwerre.

2. Pushing along the Ihiala road and exploiting

beyond Ogbaku toward Oguta.

Both of these moves were cut short by Biafran

reinforcements but served the purpose of temporarily stabilizing the situation

of what was left of the 14th and 15th brigades. Etuk’s

moves were indirectly assisted by the assault from the north on Okigwe by

elements of the First Division under Colonel Shuwa. This initially served to

distract Biafran efforts to contain Etuk.

However, reserve troops from the 13th

and 18th Brigades of the 3MCDO under Majors Tuoyo and Aliyu that

might otherwise have been available to secure the Owerri situation and stiffen

the assault on Oguta and ultimately Uli-Ihiala airstrip were diverted on a

suicidal mission to take Umuahia by the GOC, Colonel Adekunle, against orders

from AHQ. According to Major General Oluleye (rtd), this troop diversion was

done with the tacit support of the Head of State, Major General Gowon (for

details, see forthcoming essay about “Operation OAU”).

Nevertheless, during a wartime visit to Port

Harcourt, the C-in-C, Major General Gowon encouraged the 16th Brigade

Commander by radio to sit tight and hold Owerri until relieved. Like the German

6th Army at Stalingrad, the 16th Bde was ordered to

“hedgehog.” (The hedgehog is a 6 – 9 inch long mammal with white hair on its

stomach and the hair on its back modified into spines. Using the large muscle

running along its stomach it can pull its body into a compact, spiky ball for

defense purposes).

The 44th battalion of the 16th

Bde then secured the Owerri-Aba and Owerri-Umuahia roads out to 12 kilometers.

The 33rd Bn secured the Owerri-Okigwe, Owerri-Orlu and Owerri-Enugu

roads, while the 2nd Bn was stretched out securing the western

approaches to the town from Ohoba and Oguta. The 11 kilometer radius away

from the Owerri city center of the defensive lines of responsibility allotted to

the various battalions of the Brigade was allegedly influenced by knowledge of

the range (or lack thereof) of Biafran artillery. If true, it was an odd

decision, considering that Biafra had a few 105-mm Artillery pieces in its

inventory and Etuk’s troops in the city center were clearly within sniper range,

as will be apparent later in the essay. It is more likely that actual

defensive positions were functionally related to the seriousness of Biafran

pressure in various sectors. Importantly, though, supply and communication

routes from Port-Harcourt were barely protected. Meanwhile, Biafran troops

were slowly but gradually ensnaring the brigade in a noose, all the while

monitoring federal radio communications.

On each side of the 16th Brigade,

Biafran troops had successfully rolled back federal troops of Innih’s 14th

Bde to Amafor and Makanjuola’s 15th Bde to Ebocha bridge, while

sparing Etuk too much pressure along the direct northern approaches to Owerri.

Etuk – on orders from Adekunle and Gowon - would not withdraw to straighten the

Divisional line, nor did he have the resources to break out in force to attack

the flanking Biafran positions from the rear. Nor, with limitations imposed by

Adekunle’s disaster at Umuahia, was there any relieving federal assault column

aimed at Owerri towards which he could fight his way out, as Von Manstein had

tried to convince Von Paulus to do at Stalingrad, countermanding Hitler’s

orders. The 16th Bde rolled into a spiky ball, like a Hedgehog,

and waited for relief as ordered.

Thus, the wily Commander of the Biafran Army,

Major General Alexander Madiebo, one time coursemate to Major General Gowon at

Sandhurst, was presented with an irresistible opportunity to complete a classic

double envelopment of the soon to be beleaguered 16th Bde. He

accepted the invitation with humility and threw two arms of the Biafran Army

around to the rear of the Brigade in a killer Bear Hug aimed at closing the gap

along the Owerri-Port Harcourt road.

Cutting off the 16th Bde in order to

kill it